In 1992 the EEC became the European Union. Treaty of Rome was in force, family Butler ceased to be foreign aliens and became EU citizens with equal rights in Spain. Money poured in, property prices went ballistic, and Spain became the California of Europe. If we’d not risked all in 1985, we wouldn’t now be able to buy the house we lived in. I should have been happy.

I gave up a career in the UK for a simple life, now time had caught up with me. No longer pioneers, our tranquil backwater turned into boom-town where all it took was money. Freedom corrupts, even if I’d wanted to, I couldn’t return to a life in the UK. I began to think I might have made a big mistake.

Forgetting the special years we’d been gifted, I lost my way in a dark place of my own making. I started drinking too much. I became antisocial, argumentative, and rude to people I didn’t know. An arse, turning the dream into a nightmare for myself and my family.

Fortunately, Sandy was made of sterner stuff. She held things together, endured and encouraged me to take up painting. She found out about classes in the village of Selva near the town of Inca in the north of the island. The day classes were two-thousand Pesetas, including lunch. Old friends on the island, Sue and Barbara, went to the classes on Wednesdays taking turns driving, I could join them as part of the driving rota.

I resisted, I didn’t need people, I could paint on my own. But, something had to change, and I wasn’t doing anything to make that happen, I needed an incentive to get going.

Overcoming my reservations of going on some arty-farty expedition with two women, one Wednesday in late March I met the ladies outside Escarritxo church. I settled in the back of the car and watched the countryside emerge from morning fog. Almond trees, then distant grey-blue mountains appeared as the mist evaporated in the rays of the rising sun.

Outside Manacor, we turned off the Palma highway. We sped along a country road past Petra to Ariani where we turned left to Sineu and on to Inca. We reached Inca just in time to meet the morning traffic. Waiting to cross the main Palma-Alcudia artery, the ladies chatted about the things that ladies talk about, health, food, cooking, the environment and things spiritual. It was a different world to the dark place that I’d built for myself, and I started looking forward to the day. We battled through the Inca traffic onto a quiet country road and continued on to the village of Selva.

We parked in Selva on an incline close to the market square. Traders were setting up stalls and unloading vans. The faint sound of Peruvian pan flute music drifted down from a stall selling tape cassettes that was already doing business. We crossed the street to a small glass-fronted shop filled with a mix of odd chairs and paint dripped trestle tables. The shop smelled, of turpentine, linseed oil and emulsion paint, and was filled with the enthusiastic chatter of a group of ladies. It seemed I was the only male student.

Andrew, the art master, emerged from a small storeroom with a steaming kettle.

“Coffee?” he asked, but I wasn’t sure if he was talking to me, his eyes were looking slightly in different directions. It never ceased to amaze how Andrew could paint and draw so well with strabismus that must have impaired his vision. Or how he could bring one of my paintings to life just by suggesting a spot of light here or a swirl of colour there.

While Andrew prepared the coffee, I walked up to the market with the ladies. We bought some Mallorcan coca, a thin pizza topped with red and green peppers and onion. Returning to the studio, we chatted for half an hour over breakfast before getting down to work.

I’d never painted in oils, I didn’t know what I needed, and I’d brought no materials with me. Andrew gave me a pencil, rubber, cartridge paper and board. He took me up some steps to the side of a church showed me a large, old, olive wood door set in a pointed stone arch and said.

“Draw that. I’ll come for you when we go for lunch.” Then, he disappeared and left me to it.

With my arm outstretched, pencil held vertical against my thumb, I gauged the height of the door and made my first marks on the paper. Soon, I was surrounded by tourists come to visit the market. They started talking to me, wanting to know if I was an artist and if I lived in Mallorca. I reasoned, at that moment I was an artist, and so I became one. By one o’clock I’d produced a reasonable facsimile of the door. Andrew returned with the others, and we crossed the square into a side street.

In Andrew’s house, we met his wife George, and their daughters Lilly and Xesca home from school for lunch. Barbara and Sue gave George, also an artist and something of a welder, a collection of old scrap iron they’d brought from the boot of the car.

The large front room of the house, with a dining table at its centre, was full of Andrew’s paintings and George’s metalwork. One wall had shelves stacked with books of all sizes on diverse subjects.

We went up to a roof terrace to a table set for eight and had a relaxed lunch of homemade bread, lentil stew and cheese salad, followed by almond cake and cream. In the warm spring sunshine over coffee, I was surprised to learn that Andrew, George and I were all from Bedfordshire. Andrew had worked at the Cecil Higgins Museum, a place that I knew well. Strange, living so close in England, we’d never met until today’s trip to the mountains in Mallorca.

Back at the studio, Andrew assessed my sketch, determined there was hope and sent me out again with my board and paper. I found an interesting old door and settled down to draw. Sitting on a stone step in a shady street, on a mountain in Mallorca in March was a big mistake. Soon I began to freeze in the cold wind blowing through the alleyways of the village. Occasionally, a local dressed for a stroll across the Alps past me wondering why an idiot would sit in the street drawing an old door. Artists must suffer for their work, so I stuck to it until I’d made a reasonable sketch. Then, one by one, I unfolded my frozen fingers removed the pencil and returned to the studio.

Back in the warmth, Andrew gave me a minimum list of materials I’d need for my next class. It included oil paint for the primary colours red, yellow and blue, a tube of medium brown, one of black and a large tube of white. I needed a bottle of boiled linseed oil, a bottle of turpentine, a thick and thin brush, and at least one frame mounted canvas. With these, Andrew assured me I could paint anything.

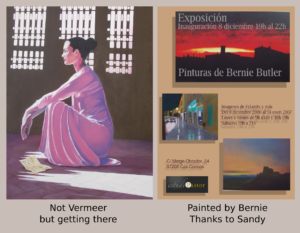

Satisfied with my day’s efforts, we left Selva that evening. I had two proficient drawings, and for the first time in a while, I was looking forward to getting on with something, I couldn’t wait to get my materials. The following Wednesday I would paint in the style of Vermeer.

In dusk’s light, we sped along Mallorca’s central plain. I watched the sunset in a blaze of gold and pink behind distant pale slate-blue mountains, and I mixed those subtle tones mentally on a pallet in my head. It was dark when we arrived at Escaritxo, and I went home to show Sandy the results of my day’s work.

The next morning, Sandy and I drove to Bendix art suppliers in Palma. Andrew told me, I could paint anything I wanted with the limited colours he’d suggested. So with rows to choose from, I stuck to the tubes of colour on the list and was amazed that I could.

I returned to Selva each Wednesday for a year, it was incredible how many paintings resulted from those six tubes. I learned much from Andrew, not least to listen. We had great times until Andrew’s work made it difficult to continue the classes. George never produced a bad meal, and I doubt if Andrew ever made a profit. I might not have been the new Vermeer, but I was happy enough with my efforts.

We had great lunches on the sun terrace sharing memories of characters and places around Bedfordshire. It certainly is a small world. But I wouldn’t like to paint it.