The union shop-steward and the chicken.

The union shop-steward and the chicken.

In 1984 my partner and I sold a 160kV microfocus X-Ray system, to Rolls Royce Aero Engine Division at Coventry Parkside, for inspecting critical parts of the Tornado multi-role combat aircraft. It was quite a coupe because we were only a two-man company. Unions were powerful in the UK then, and before you were allowed on the shop floor in Rolls Royce, you had to have a union card. I didn’t have a card, so I joined TASS, the Technical, Administrative and Supervisory Section of the AUEW (Amalgamated Union of Engineering Workers). Things should have been simple, but British workers were a belligerent lot. Especially, as Maggie Thatcher was having a showdown with the Miners’ Union at that time.

For some reason I didn’t understand, neither I nor my equipment was welcomed by the workforce at Parkside. I got a very frosty reception from the staff in the X-Ray Department. The head of department, a straight-talking Yorkshire man, named Don Botham, was pleasant enough. However, the rest of the workers led by a union shop-steward named Kevin were openly hostile and uncooperative, and no one spoke to me, at least not civilly. I was ostracised, sent to Coventry in Coventry.

The industrial microfocus was in its infancy then, and it was cantankerous at the best of times. Trying to set one up in an industrial environment with an obstructive workforce was near impossible, it was a very uncomfortable situation. Each day I made the one and a half-hour drive from Flitwick to Coventry, for an unpleasant day at Rolls Royce, and dejected, I made the long journey home in the evening.

To develop and market the microfocus my partner and I had a £40,000 unsecured loan from the British Government, which had to be repaid in two years at 16% interest. To get that loan we had to match it with our own money. Sandy and I didn’t have £20,000 for our half, so we took out a second mortgage on our home to cover it. There was more riding on this order than my hurt feelings.

I’m an easy-going person, and it takes quite a lot to upset me, but one thing that will do it is being treated unjustly. It’s something I inherited from my Irish mother. The concern about repaying my mortgage, combined with the unfair treatment I was getting from the shop-floor had pissed me off.

One lunchtime while working in the X-Ray room after a horrible morning, I snapped.

I don’t like conflicts, but I was in an ‘I don’t give a f**k’ mood and I wanted to confront the shop-steward by himself. I waited in ambush for him in an alcove in a corridor from the works canteen where I knew he would return from his lunch. As he passed, I pulled him in.

“What’s your problem, Kevin?” I demanded.

After he got over the surprise, he responded.

“You! You’re my problem. That machine of yours, it gets the work done too fast. It’ll put us all out of a job”.

“So that’s it! Well, I can tell you, when I was with Scanray, I put two of these machines into German factories. The Germans are working on the Tornado too, and they’re going flat out. If you don’t start working with this equipment, you will all be out of a job, and the work will go to Germany. So you better think about that”.

Once I recovered from the adrenaline rush, I packed my things and left.

The next day I stayed at home, I couldn’t bring myself to return to Coventry. The following day I’d summoned the courage to go back and face the music.

Early morning, when I walked into the X-Ray Department, there was a palpable change in the atmosphere, I was greeted like an old friend. Kevin said they were making tea and toast and would I like some. It would have been churlish not to, so I joined them in the staff room. They’d discussed the issue, and I was now part of the team. That’s how a conflict turned to friendship.

Three years on, the Butlers were living in Mallorca renovating an old farmhouse. Occasionally I flew back to the UK if Rolls Royce had a problem. We didn’t have a telephone, but Mike Brown, an 80-year-old American in the village did. Mike would cycle down to our house with messages, and I’d use his phone to call back. I got a call from Kevin one day. He was coming to Mallorca on holiday and wanted to visit us to see what we were up to. We arranged a rendezvous. On the day I met Kevin, now Kev, and his wife Bev in the Palm Square in Felanitx. They followed me in their hire car through the lanes home for lunch. Like all of our first-time visitors, in its setting close to the Monastery of San Salvador and the Castillo de Santueri, they were struck by the tranquillity and rustic charm of Cana Cavea.

As usual, Rohan had conveniently forgotten we had guests for lunch and was nowhere to be found. He could have been anywhere in a three-mile radius, but it was a good excuse to show Kev around the extended village of Son Barcelo. Kev and I set off in search of my boy leaving Sandy, Bev and Tayrne preparing lunch. We took the old back road and ended up in Cas Concos. Ahead of me in the village, I saw some boys I recognised standing in the arched doorway of a garage. As I approached, one of the boys turned sideways and, with a hand over his mouth, spoke into the garage. I stopped the car and got out.

“¿Toni, visto Rohan?” I asked

“No” came the reply with a characteristic wagging index finger and a ‘tick’, ‘tick’ tongue click. I knew he wasn’t telling the truth. I put my head into the garage but saw no one in the dim interior. Both doors were folded back against the walls, the one to my right was slightly angled out, I leaned up against it, nothing. I pressed a little harder, after a few seconds I got a response “Oh dad”.

I let the pressure off, and Rohan’s head popped out from behind the door. He never seemed to understand his dad was a kid once.

“We’ve got guests for lunch,” I said, “Now, get in the car”.

As we left, I wagged my finger at Toni and gave him the double tongue click.

“Kevin meet Rohan,” I said as we drove back to Son Barcelo.

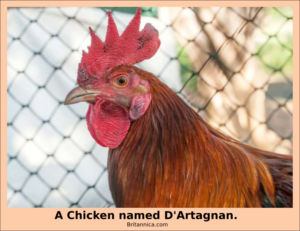

At this point, I have to tell you about our attempt to live the good life on a smallholding in the Mediterranean. Early on, we bought three chickens, the hens were called Ethel and Myrtle, the cockerel D’Artagnan. As each new clutch came along, they all got names. Unfortunately, we found it impossible to kill chickens with names. For a while, we even had trouble eating their eggs, it seemed like cannibalism. We ended up with thirty chickens that became part of the family. Now, these chickens might have been stupid birds, but they always knew when it was lunchtime.

We sat down to eat in the shade of the front terrace. It wasn’t long before there was a cluck clucking and around the corner of the old bread oven wandered D’Artagnan with that strange staccato walk that chickens have. Soon, he was followed by the rest of the brood. I noticed Kevin had gone very quiet and thought he was taking in this enchanting pastoral scene. I was about to chase the chickens away so we could get on with lunch when D’Artagnan flapped wildly and sprang up and sat on Kevin’s lap. For a moment, Kevin sat frozen in his chair, then in a frenzied voice, he shrieked.

“Get it off me, Get it off me”.

D’Artagnan, not the most valiant of birds, squawked and went into convulsions. He battered Kevin’s face with flapping wings, made his escape and disappeared around the corner clucking, followed by the brood. I thought Kevin, ashen-faced, was going to pass out. He was shaking, so I jumped up and offered a glass of red wine to revive him.

“What in heavens happened?” I asked.

When he’d calmed down, he replied: “Sorry, I’m terrified of chickens”.

I looked at him astonished. I found it bloody hilarious, I just couldn’t help myself.

“Do, you mean to tell me, all that crap you put me through in Coventry, and all I had to do was bring a chicken with me to get some cooperation?”.

We had a lovely afternoon, and our guests went off with a new insight into the island of Mallorca.

Strange though, I never saw or heard from Kevin again.

Alektorophobia, the fear of chickens.