The fortunes of an apprentice.

The fortunes of an apprentice.

By September 1967, I had completed one year of my apprenticeship at Headley’s Engineering in Dunstable. It had been a bit of a struggle. I started off riding to work every day on my Vespa 150 Sportique, a round trip of 48Km. After about six months, the clutch went. On my wages of three pounds ten shillings a week I couldn’t afford to get it repaired. While full time at college, I’d worked weekends, bank holidays and during the term breaks, at the Granada Motorway Service Station at Toddington, to get the money to buy that scooter. Sometimes I worked sixteen-hour double shifts clearing tables or working in the grill as a commis chef under Mr Charles the big West-Indian head chef.

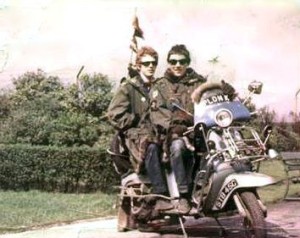

That silver-grey scooter with chrome side panels and trim cost me one hundred and forty-five pounds, now it was a mouldering heap of junk in the back garden. Initially, I’d been saving to buy a 250cc Royal Enfield Continental motorbike. However, while working late shifts at the Granada at weekends, after the pubs shut the cafe would fill with revellers looking for something to eat. I noticed that the large groups of macho motorbike Rockers that came in usually had only one or two equally hard-faced females with them. In contrast. The well dressed Mod boys on their scooters in smart suits, Hush Puppies, Ben Sherman shirts, fancy haircuts and parkers were always accompanied individually by a well turned out, stylish young-lady. To the consternation of my mates, I bought a suit, got a haircut and purchased the Vespa.

It was ironic that now I was in full-time employment, I had less money than when I was studying and working part-time.

However, I was fortunate, I lived close to the M1 motorway. With no scooter, every morning I would walk the 1Km from home to junction 13 and hitch a lift to Luton, catch the bus from the Hospital to the centre of Dunstable and then walk the last 1.4Km to work. I would do this again in reverse every night to get home. Generally, it worked alright, I became known to a lot of drivers going to and from Luton.

However, I wasn’t always lucky, occasionally, when it was hard to get a lift, I might not get home until gone ten at night. I did that every day for three and a half years. To say the least it was character building especially in the rain and snow of winter. Towards the end of my apprenticeship, I even got offered a job by the MD of Hillmax Engineering. At the time, I didn’t realise it, but that interview had been conducted over a period of three years! In the end though, I decided I’d had enough of factory life, and I went off to sea looking for some adventure.

Headley’s, had a canteen where you could get a subsidised lunch, but my wages didn’t stretch to that, so every day my mum would make me sandwiches to take to work. That’s when the mother of another apprentice, my mate Robin, stepped in. Mrs Beagarie, took it upon herself to make sure that I got one cooked lunch once a week. Every Friday I went the few hundred metres from the factory to Robin’s house for lunch. We’d have wholesome food like Sausage and mash, Steak and Kidney pie and desert. However, what I enjoyed best was when Mrs Beagarie served battered cod, chips and peas followed by chocolate mousse.

Unfortunately, although I wasn’t starving, my financial situation was quite desperate, Robin’s wasn’t that good either, so we formed a business partnership. I’m sure Robin will correct me here, someone in his family, his brother-in-law I think, worked at the London Rubber company. He could get us a gross box of condoms for half the street value. That was 48 packets of 3 for a total cost of 7 Pounds 10 Shillings. At that time condoms were sold at 3 Shillings 9 Pence (3s/9p) for a pack of three. If we sold our condoms for 2 Shillings 10pence (2s/10p), 25% below the street value, we would make a profit of 3 Pounds 16 Shillings and 8 Pence on every gross box we sold. That was equivalent to more than a week’s wages to split between us. The start-up cost was big money to us, but we got it together and went into business. After the first weeks’ trading in the factory, we had sold over half our stock. We intended to plough the profits back into the business and buy more condoms. The only problem I had was if my Irish Catholic mother found out that I was selling contraceptives, I’d be excommunicated. Condemned to burn in hell, I’d have been better off selling drugs.

Happy with our first weeks trading. Before we left work on Friday, we put our remaining stock and our takings into the tool cupboard by Robin’s milling machine. However, unbeknownst to us, there was a cloud on our horizon. Roe Wilson, the factory foreman, had been keeping an eye on our activities. As soon as we got into work the following Monday morning, we were called into the foreman’s office. He opened his desk drawer and placed our Durex Gossamer box, with the remains of our stock and our takings onto his desk.

“What’s this?” he asked

Robin and I stood in silence for a moment, confused.

Surely he knew what condoms were.

“They’re condoms,” we told him.

“I know what they are. What are condoms and this money doing in your cupboard?”.

We told him it was a little business on the side to help with our finances.

He gave us a right dressing down.

“Your indentures explicitly forbid you from engaging in any other trade or business while you are employed as apprentices with this company”.

We were told to take away our stock and money at the end of the day, and not to run a business inside or out of the factory.

God! they were only condoms, maybe he was a Catholic.

So that was the end of the Beagarie-Butler condom sales empire. Still, at least we had a supply of inexpensive condoms if we ever got the opportunity to use them.

Another missed financial opportunity was related to my skill at picking winning racehorses. A machinist named Tom Drew, who lived in Luton, on occasions if he wasn’t doing overtime, would give me a lift to the M1 motorway on his way home. One night, while giving me a lift, he stopped off at the bookies in Church Street. He was going to put a one shilling bet on three horses. Just for a laugh, he said he would let me choose one horse, and if it won, I could have half the winnings. He showed me the board for a race that was coming up in a few minutes at Kempton Park. I didn’t know anything about racehorses, but as I looked down the list, one horse caught my eye.

“Prince of Verona,” I said.

I loved Shakespeare ever since seeing the Merchant of Venice in Shaftesbury Avenue London, on a trip from Fulbrook School.

“Thirty-Three to one! That hasn’t got a chance in hell of winning” said Tom.

“You said to choose a horse, that’s the one so put the bet on”.

Tom shrugged and against his better judgment put on the bet.

The radio in the shop crackled to life as the race started. There was no mention of our horse until just before the end of the race.

“And here comes Prince of Verona.”

Tom and I were jumping up and down hugging each other in excitement. The commentary continued.

“It’s Prince of Verona challenging now. Prince of Verona, Prince of Verona. Yes! At the line by a head, it’s Prince of Verona.

Tom looked at me in consternation, he went up to collect the winnings and true to his word; he paid me sixteen shillings and sixpence.

The next morning at work, I was famous. At tea-break, I was confronted with a newspaper to pick the winners for that afternoon’s race meetings. I protested, but I was forced to choose the winners. I had no clue, I just went down the list circling anything with a pencil that took my fancy. At lunchtime, someone went down town with a pile of money and put on everyone’s bets. In the afternoon, a transistor radio, on low and away from the foreman’s office, kept track of the results. Not one horse came good, everyone lost their money. That was a real case of ‘from hero to zero’.

So ended my career as a clairvoyant.