Our house, named ‘The Wild Olive’, is in a rural setting a few kilometres from Felanitx. In the Mallorquín-Catalan dialect, it’s called ‘Els Ullastres’.

A low hill with trees buffers us from the town so you wouldn’t know it existed. That is, except for the week of Saint Augustine in August. In that week, the verbenas are held. The Municipal Park becomes packed with locals and visitors from across the island, and our pastoral tranquillity is immersed in Gigawatts of Rock music from dusk until dawn when the nocturnals retreat to their beds to prepare for another night of fiesta.

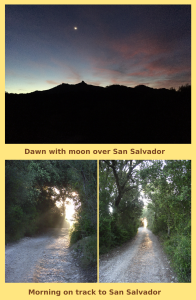

It’s a small price to pay for the warm evenings when we sit beneath a star-filled sky, with the long phosphorescent cloud of the Milky Way stretched out above us, and only the tinkle of sheep’s bells and the hoots of hunting owls to disturb the night. I digress. What I mean is, Sandy and I live in a beautiful quiet spot below the monastery of San Salvador.

I have high blood pressure, and my Spanish National Health doctor, Doctor Morant, tells me I should take regular exercise. So, most mornings, I make a four-kilometre walk, up the lane through the woods to the crucifix at the bottom of San Salvador and back home again. I have been known, on extremely rare occasions, to continue to walk up the ‘goat track’ to the top of the mountain. There, to take a morning coffee, marvel at the beauty of the island and the Mediterranean from this vantage point, then walk back down the mountain to home.

On the morning of 24 September 2019, I set off at 07:30 on my walk. It’s an excellent time to exercise, daylight and cool, with the sun still to the east behind the mountain. After a kilometre, the track levels off and the way is blocked by a gate. The gate was put there years ago, by the farmer who owns the land. Some local pyromaniac set fire to the pinewood and almost burned down the mountainside along with a few houses. From there I went to the left, where mountain-bikers have beaten a trail through the pines, down into the dry torrent and up the other side to another track running up to the monastery.

As I walked in solitude, I inexplicably wondered if I had any regrets about bringing my family to live in Mallorca all those years ago. I came to the conclusion that my only regret was that I had never become fluent in Spanish. That is not to say I don’t get by, I have made a lot of Spanish friends over the years, although these days most of the younger ones prefer to practice their English. I remember a few years ago sitting opposite a German lady in a restaurant explaining this exact same woe. She looked at me and said:

“You English are all the same, you are so lazy, you never learn to speak another language”.

I was deeply offended. I’m Irish!

Although what she said was generally true, I was angry with her for not being sympathetic when I was explaining my dilemma. I sat for a moment, and then completely from nowhere and not even thinking about it, in one rush of words, I came out with:

“Alle Deutschlanders denken, alle Englander sprechen kein Deutsch. Aber das es nicht richtig. Ich spreche Deutsch, aber es ist eine lange zeit wen letzte ich arbeit en Deutschland und jetzt mein Deutsch ist nicht so gut. Aber wenn ich bin oft mit Deutschlanders und spreche oft mit Deutschlanders, dann mein Deutsch ist besser”.

I believe what I said was:

“All Germans think all English don’t speak German. But that’s not right. I speak German, but it has been a long time since I last worked in Germany and now my German isn’t so good. But, when I am often with Germans and speak often with Germans, then my German becomes better.”

It might not have been Hochdeutsch, but she understood me. What I found difficult to comprehend was how it had all come out simply because I was angry with her.

I walk on pondering the strange phenomenon of language. How could it be that without understanding the grammar or verb structure, you could communicate with someone in another language? I came to the realisation that when I spoke to anyone in Spanish, I actually had no idea what I was saying, only what I thought I was saying. That is a bizarre concept to grasp.

Before I knew it, I came out of the woods and onto the tarmac road that goes up to the monastery. This is the best part of the walk. From here, sitting on the round stepped base of the three and a half metre high stone crucifix, you can see right across the sixty kilometres to the other side of the island. As I sat gazing towards the far Serra de Tramuntana mountains emerging through the morning mist and considering what I had been thinking about on my walk, a strange thing occurred.

Coming up the hill, from the main road below, was an old man. Very close to where I was sitting was a van, where a young man was preparing himself to jog up to the monastery. The approaching old man crossed the road, I thought he was going to talk to the man by the van, but he didn’t. He walked straight up to me.

In Castilian Spanish, not Catalan or Mallorquín, as if he knew from my appearance that I was a foreigner, he greeted me with a ‘Buenos días’ and introduced himself as Antonio Barcelo Bordoy. He spoke quite slowly and deliberately as if he had suffered a mild stroke.

In turn, I introduced myself to him, and we spent the next fifteen minutes in idle conversation. During that time, I learned that he was seventy-five years old, he was a retired farmer and that some years ago he had fallen from a stone wall. He lay unconscious all morning until his son, realising he had not returned for his lunch, went and found him. He had spent two months in the Hospital Juaneda Miramar in Palma where they had drilled his skull to relieve the pressure on his brain, following which he had six months of rehabilitation to learn to walk and talk again. He showed me the scar on the right side of his head. He lived in Felanitx, and his wife had died four years ago. He had two sons and two grandsons who were now grown men. He liked dancing, but he was no longer allowed to drive because of his disability. In turn, I told him I was seventy years old, that I had lived in Mallorca for thirty-three years with my wife and two children who both had Mallorcan partners and we had five grandchildren, three boys and two girls and another boy on the way, due in October. I told him I was born in England, but that all my family were Irish. As we chatted, we discovered that we had three mutual friends:

My great old farmer friend Juan Bennassar, who lives on the road up to the Castillo de Santueri;

Guillermo, who owned the señorial house at the entrance to our lane that has now been sold to an Argentine; and

Miguel Cummis, the old electrician who was our neighbour when we first lived in Son Barcelo.

Between us, we figured that Miguel had died eight years ago and lamented how fast time flies.

We parted company the greatest of friends, hoping to meet again in the future on our paseos.

Antonio made his way back down the hill to Felanitx, and I took the camino back through the woods to The Wild Olive.

My son Rohan believes that you can draw good or bad to you merely by your mental state. I see his point, but I believe life is more a series of random quantum events over which we have little control. After all, the probability of meeting an old Mallorcan farmer who enjoys a chat, on a walk near the monastery of San Salvador is pretty high, there’s no mystery in it. Never-the-less, it was curious that I had such a long dialogue with Antonio when I was only just contemplating my inability to converse in Spanish.

Someone once told me that, language is just a system by which we humans communicate. It’s more complicated than just words, it involves attitude, gestures, subliminal signals and possibly a lot more. Ultimately, it comes down to communication by whatever means is available.

In reality, many people who speak the same language don’t understand what the other person is saying; anyone who’s married knows this to be true.