Granddad Butler

Granddad Butler

“Oh! Granddad, I can’t do it. I’ve tried, and I’ve tried, but I can’t do it, show me how”.

The rebuke came in a sympathetic but firm Irish tone.

“I will not. What benefit would it be to you if I just show you how to do it? None at all”.

He stretched out his arm and tapped the top of my head with his index finger.

“What do you think that’s for, why do they teach you trigonometry and geometry?”.

I was eleven, sitting across the table from my grandfather in my Auntie Mai’s restaurant by the clifftop where the Wexford-Dublin road comes up from Rosslare Harbour.

Earlier, Granddad Butler had placed six matches on the table and said.

“Make four equilateral triangles. And no, you can’t break them into shorter pieces”.

He always gave me puzzles and as much as I pleaded, he wouldn’t show me how to solve them. He didn’t do it to prove he was smarter than me, he did it so I would think for myself. He was cryptic, he didn’t use words lightly, words were important. There was a clue in his words, but like the puzzle, you had to work it out.

I stared at the matches on the table. Triangles were trigonometry, equilaterals had three equal sides. Why did he say geometry? Then, there it was, the answer as clear as day.

“Granddad.” I said “I’ve done it. That was a trick question”. Of course, it wasn’t a trick question, just a problem that needed some thought.

I looked into his turbid, pale-blue eyes. He smiled, then just so I didn’t get cocky.

“Brothers and sisters I have none, that man’s father is my father’s son. Who am I?”.

“Granddad, stop it. I’m on holiday”.

17 March 2020, as I write this, it’s the funeral day of Sandy’s mother, Nana Dolly to the kids, she was 94. We were to fly to the UK last Saturday, but due to the Coronavirus pandemic, we didn’t. However, Sandy’s brother Derek set up a video link so we could follow the church service live. Today is also St Patrick’s Day, a great day for the Irish. It’s to soon to write about Nana Dolly, so I’ve decided to write about my grandfather instead.

Tomorrow is an important day for another nation. 18 March, is Martyrs’ Day in Turkey, Remembrance Day for the tens of thousands of their sons who gave their lives in the Battle of Çanakkale. On that day in 1915, only 24Km across the Aegean Sea from the ancient city of Troy, a combined British and French fleet launched an attack at the narrowest part of the Dardanelles strait at a place known as Gallipoli. The attack didn’t go well, ten days earlier the Ottoman ship Nusret had mined the channel. After the sinking of three battleships and severe damage to others, the attack was abandoned. So, what has this to do with my grandfather?

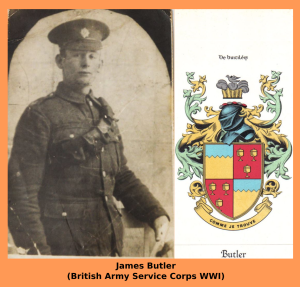

24 April 1915, a 21-year-old Irishman, James Butler, newly enlisted in the British Army’s Service Corps, was a long way from home in Egypt. A day later, British forces landed at Cape Helles, totally underestimating the spirit of the Turkish Ottoman troops and the quality of their leader. Colonel Mustafa Kemal Pasha, later the 1st President of modern Turkey, had predicted exactly where the British would land. When they did, he issued this chilling order to his men.

“I do not order you to fight, I order you to die. In the time it takes us to die, other troops and commanders can come and take our places”.

And so my grandfather became embroiled in one of the bloodiest battles of the First World War. His rank was Driver, the T in his service number T4/061496, indicates he was with ‘horse transport’. His job was to move provisions by pack animal to the front lines to keep the troops supplied. My father called him a ‘mule skinner’.

On 9 January 1916, over 10 months after the first naval engagement, having achieved nothing other than the death of 56,000 of their own and 65,000 Turkish troops the British Empire forces withdrew.

My grandfather never spoke to me about the war. I always assumed he’d lost his sight in a gas attack at Gallipoli, but I was wrong, the Turks never used chemical weapons there. It was years later when my cousin, Jim Greenslade, sent me a document from the forces war records that I realised what had happened.

After Gallipoli, the British Army decided my grandfather’s services were needed in Belgium. I hadn’t even known he’d been on the Western Front.

On 18 July 1917, he found himself in the 5th Army Ophthalmic Casualty Clearing Station, Ypres. After treatment for trachoma, on 29 July he was transferred to a Hospital Ship.

Two days later, 31 July 1917, the Third Battle of Ypres, also known as Passchendaele, erupted. After more than 3 months of fighting the British had advanced only 5 miles with the loss 275,000 men killed, wounded or obliterated from the face of the earth. The Germans are estimated to have similarly lost 220,000 men. The Menin Gate and Tyne Cot Memorials together bear the names of 89,400 British and Empire servicemen who died in Belgium and have no known graves.

And so my grandfather didn’t lose his sight in a gas attack. He lost it from untreated trachoma contracted in the unsanitary conditions of the trenches or from the sands of Egypt. Ironic as it sounds, blindness probably saved his life.

Granddad Butler came out of the army in 1917. In 1918 he married Ellen Stone from Waterford, they had ten children. I can only remember meeting my grandmother once around 1952, when I was 3 years old. My family took the train from Rosslare to Waterford and stayed overnight at 30 Rathfadden Villas, a terraced house built by the British Legion for ex-servicemen.

My grandfather was fortunate, in early 1915 Sir Arthur Pearson, author of Victory Over Blindness, himself blind, founded the St Dunstan’s Hostal for Blind Soldiers and Sailors. Established in Regent’s Park, it was a place where blind servicemen went after hospitalisation. The legacy of the war meant that as late as 1929, there were still two thousand men in their care. My grandfather was taken in by St Dunstan’s to ‘learn to be blind’. They taught him to read and write and tell the time in braille. He became an incredible basket maker, making anything in wicker: chairs, tables, storage trunks, hats, children’s toys even rocking-horses.

When he moved from Waterford to Rosslare, he named his house Ozier Lodge after the long willow shoots that are grown especially for basket and furniture making. I have such fond childhood memories of staying with my Granddad Boyce at 1170 Colville Street and of wandering down the lane to Ozier Lodge to watch Granddad Butler doing his basket work. I even made a small basket myself once under his guidance. He was so clever with his hands. He made the most fantastic Chinese puzzles out of wire coat hangers. One he called the trapeze artist; at one end there was what looked like a stirrup with a trapeze bar through it with two bent ring ends so it couldn’t come out of the stirrup. Connected to the stirrup was a series of five or six different shaped links that hung down like a chain. The object of the puzzle was to move the stirrup and bar from one end of the chain to the other. My grandfather could do it so fast that I could never figure out how it was done. It was one of his puzzles I never solved. So famous was this puzzle that one time a crew from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation turned up at Auntie Mai’s restaurant to film Granddad and his creation.

I guess being blind at 23 must have caused a lot of trauma in his life, but I never saw any of that. What I remember is a very calm, confident, skilful man with a mind as sharp as a razor.

James Butler’s luck ran out on the 16 March 1968. When he was 74 years old, he was killed in a traffic accident in Ireland, on the same day that my sister Ellen was married in England.

There are many mottos on the various Butler Coats of Arms in Ireland. The one that was in my Auntie Mai’s restaurant in Rosslare read ‘Comme je trouve’. In Kilkenny, where my grandfather came from this is interpreted as “I take and make life as I find it”.

That motto epitomised Granddad Butler’s attitude to life.

2 Responses to Granddad Butler