27 September 1985. The wipers rasped monotonously back and forth against the driving rain. I stared out at three rows of taillights that stretched to infinity in the darkness.

I’d spent the whole week working at Howmet Turbine in Exeter. Now, after 180 miles and nearly five hours fighting Friday night traffic on the M3 and M25, I was trapped on the M1 motorway just 20 miles from home and my family.

A full-face-helmeted, leather-clad motorcyclist squeezed by my right side. He jiggled his machine around the front of my car, accelerated up the hard shoulder and disappeared into the night on the Hemel Hempstead slip road. That was it. I slammed my hands onto the steering wheel.

“Fuck it, fuck the money, I am not doing this for the rest of my life”.

When I got home, I said to Sandy.

“There’s no way we’re ever going to finish that farmhouse in Mallorca unless we go and live there.”

“OK,” she said.

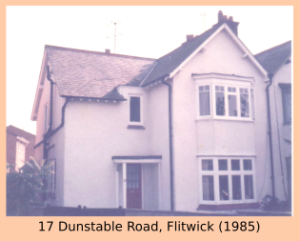

On 11 October 1985, 17 Dunstable Road, Flitwick went on the market. The following three months were depressing. We were told we were asking too much, but the price was critical for the success of the venture. Things picked up after Christmas. Calculating it would be just enough for our needs, we accepted a lower offer, which fortunately fell through.

In early March, a man who bought and sold steam locomotives worldwide made an offer close to our asking price. On 13 March 1986, while I was working in Windsor, Sandy signed contracts. We had until the 21st to vacate.

The decision to go had been simple, the implementation was something else. During those days, the overriding emotions were fear of the unknown, with moments of elation about starting on a fantastic journey. I remembered the same feelings when I joined the Merchant Navy while waiting to fly out to join my first ship in India. This time though, there was more than just me to worry about. At night, I was kept awake by the constant rumblings of the cement mixer churning things around in my head.

‘Clear the junk, pack what we’re taking. The kids’ education. Should we take the piano? Should I tell the MoD Bromley and Rolls Royce? No, they’ll think I’ve lost the plot’. Details details details.

A further complication, I’d been offered the position of Technical Director of Goring Kerr Detectors plc with an insane salary and the whole inducement package. A job I hadn’t even applied for. Most people would have taken it, I turned it down. Maybe I had lost the plot.

Sandy’s dad (Dad), always good for a deal, got a job lot of pine crates from his mate who imported Russian equipment. I had a premonition. I was summoned to Spanish customs to witness the opening of my containers stamped CCCP with the hammer and sickle, euphemistically marked ‘Machine Parts’ to find them full of AK47s. Dad’s mate also offered to hire us a lorry, cheap.

We discarded or sold what possessions we could, wrapped what remained in newspaper and packed them into cardboard boxes scrounged from local shops. Each box was numbered and its contents recorded on a five and a quarter inch floppy disk using my, 12K RAM-12K ROM, BBC Acorn Atom computer. Then, the boxes were loaded into the Russian crates in our garage.

On 19 March Dad and I went to Bedford to collect the lorry. We got there at 17:00, but the truck was still out on a job. At 19:00 Dad’s mate phoned us at home to say the lorry had broken down and we’d have to pick it up at 08:00 in the morning. We had to be at White and Co International Removals in Bournemouth at 15:00 the following day. With no lorry, our consignment was still on the garage floor. It was time for a nervous breakdown.

The next day we arrived in Bedford at 08:00 to pick up the lorry. It was still under repair. When we got it, it looked like something that might have been abandoned by the British Army on the beaches of Dunkirk, but it was too late to find an alternative. It was raining when we got to Flitwick at 09:30. My brother-in-law Gary came to help lift the heavy crates. The phone never stopped ringing all morning, but at 10:30 it did at least stop raining. By 12:30 we were loaded and Sandy’s brother Derek, Dad and me were on the road. After a painfully slow acceleration phase, we came to the stark realisation the lorry was governed to a maximum speed of 45mph. If we maintained that speed, we’d arrive half an hour late in Bournemouth. Owing to its struggle in climbing the slightest gradient and its inability to make up time on the down slopes due to the governor, we had to extend that ETA. Our only hope was that White and Co would stay open and not close up shop before we arrived. We crawled into our destination at 16:30 hrs, and I gave the workers ₤5 for a drink to quiet their grumbling. We had an unmemorable meal on the M27, our first of the day. At 19:00, we were back on the road. Having become familiar with the elusive 3rd and 4th gears, Dad threw the now empty vehicle into the dark night. After four gruelling hours, with our house in Flitwick vacated, we arrived exhausted at Sandy’s parents home in Marston. There we would stay until we left for Spain in a months time.

A few days before we flew to Mallorca. I packed up my computer, monitor, daisy-wheel printer, floppy-disk drive and the other stationery and office equipment I was using to run the business. Sandy and I filled the back of the Mini Metro and made our last trip to White and Co. After the drop off we left Bournemouth heading for Tidworth 27 miles away to visit an old friend. Ray and I had known each other since we were kids, we were godparents to each other’s children. He’d joined the army at fifteen and a half. He’d been with 22 SAS in Hereford from the age of nineteen, where he’d risen from trooper to sergeant, to Warrant Officer. In 1985 he became a commissioned officer and was now stationed at Tidworth. Arriving at Tidworth House, we were confronted with a 4-ton Ferret scout car with a Browning Machine gun sticking out of its open turret manned by a soldier. The vehicle was guarding the open courtyard to the Officers’ Mess. 30 metres into the yard two officers stood chatting on the entrance steps to the house. As we were halfway into the courtyard, to our right, through the window of a lit room, Sandy saw Ray working at his desk. Fortunately, out of sight of the Ferret, she did no more than step over the low chain and post boundary, ran across the lawn and banged on the window. This didn’t go unnoticed by the two officers. I cringed, this was the British Army. I decided to walk on and make a proper introduction. I was wearing denim jeans, my hair was shortish, but I was due for a haircut, and I had a moustache. I ambled up the steps with my hands thrust into the pockets of my brown leather bomber jacket, against the cold night air. At the top, I said casually. “I’ve come to see Captain Raymond Papworth”.

For a moment, the two officers gave me a slow up-down-up inspection. Then, the one closest to me, with a slight shake of the head and unconcealed disapproval said, “Tch. Obviously SAS”.

I was flattered by the mistake but never said anything to destroy the illusion.

By this time, Sandy was coming up behind me, and Ray appeared at the entrance door. After a short reunion with tea and cakes in the mess building, the three of us left for Andover for an India meal before Sandy and I returned to Marston.

Following the sale of 17 Dunstable Road, we paid off our house mortgage. We also paid off the second mortgage we’d taken out to start the business and transferred the money to pay our outstanding bills in Spain.

After this, we were left with thirty-four thousand one hundred and fifty-six pounds, and eighty-five pence. It didn’t seem like an awful lot of money for what we intended to do. But we had no debts.

Regardless. We’d crossed the Rubicon. There was no turning back now.