Our friend Juan in the Guardia Civil. Part 1.

Our friend Juan in the Guardia Civil. Part 1.

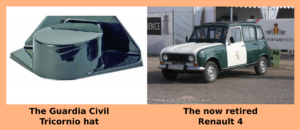

People who have visited Spain are probably familiar with the Guardia Civil. Older tourists will remember when they wore the tricornio, the shiny black, three-cornered hat. Before my first trip to Spain in 1968, in the Franco era, I was advised not to mess with the guys who wore that hat.

Some people, myself included, saw them as the muscle behind Franco’s rule. That may be true, but, formed in 1844, the Guardia Civil is, in fact, Spain’s oldest national law enforcement agency.

Another common misconception is that because one of its symbols is a bound bundle of wooden rods holding an axe, it was a fascist organisation. The fasces is an ancient Roman symbol of unity, being adopted by the Italian Fascist Party, did not make it a fascist symbol. It might surprise some to know that the Guardia Civil was the first European police force to allow a same-sex couple to live together in a military installation.

I’m not an expert on the history of the Guardia Civil, but I do have first-hand experience of them in a modern democratic Spain. So on with the story.

Arriving in Mallorca in April 1986, we really had no idea how this experiment would evolve. We sold-up in England to fund the venture but didn’t entirely burn our bridges. Initially, I travelled back and forth to the UK to work and maintain my work connections. That was intended to be a short-term solution until we were established on the island if that was possible. We gave ourselves two years to make a go of it, if it didn’t work in that time, we’d sell up and go home.

Hopefully, by then Spain would be in the EEC. Cana Cavea would be renovated, property prices would have risen, and northern Europeans would be buying. That, reluctantly, was our Plan B.

We should have registered with the authorities as permanent residents in Spain. That involved a lot of time and expense and a stressful paper-chase that would be pointless if we returned to England. While I was working and in continual transit between Spain and the UK, we decided not to register. Technically we were illegals! However, it wasn’t that simple, the children needed an education. We had made the decision that our children would not be educated in the English speaking international school in Palma. If we were going to live in Spain, our children would go to a Spanish school. The Spanish Constitution was quite clear, children from the age of five must attend school, but interestingly it didn’t specify the nationality or legal status of the children.

In early May I was working in the UK. Sandy, our neighbour Maria, and our new friend Lynn Hart who spoke Spanish went to Felanitx to enrol our children in Juan Capo School. Residence papers weren’t asked for, but there was a problem. The head of the Parent Teachers Association objected to having two foreign children in the school. They couldn’t speak Spanish, let alone Catalan, and they would disrupt the education of the local children. They would have to take Spanish lessons for six months and then reapply. Sandy retorted, in that case, she would put them into the village school in S’horta that Lynn’s two girls attended. At that point, Isabel the Head Mistress intervened, she saw the benefit of two English children in the school. They started school the following day.

Near the end of June, the school closed for the long summer recess, and we went to see Isabel to find out how the children were doing. Isabel happily said that after less than two months, you could no longer pick our children out as being foreign. And so, one of the biggest hurdles to our living in Mallorca was overcome. Thus began the Spanification of our children, and the integration of family Butler into Mallorcan society, resulting in some surprising long and short term consequences.

Summer passed, and the children returned to school, winter came and then it was 1987.

One Saturday, Rohan asked his mother if she could take him to Felanitx, he had been invited to stay at his friend Jorge’s home for the weekend. When they arrived in Felanitx, Rohan asked Sandy to drop him off. Sandy refused, she needed to know where he was staying. Rohan said it was like a hotel and reluctantly directed her to the highest part of the town. At the top, she drove around the side of a large, austere building, and found herself parked on the parade ground of the barracks of the local Guardia Civil.

When Sandy returned and told me where Rohan was staying, I almost had a seizure. It transpired that every day, Rohan and his friend Jorge bought sweets with Rohan’s dinner-money. They then went to the Guardia Civil barracks for lunch with Jorge’s parents and younger brother. They wouldn’t need to pull me in for questioning, Rohan would have already told them everything. What were we going to do? We would have to sweat this one out. At least assisted truancy wouldn’t be on the charge sheet.

5 February 1987 was Tayrne’s ninth birthday, she was going to have a big party at our house with her friends. Rohan was allowed to invite one friend, inevitably, he wanted Jorge. I saw two problems. One, Jorge’s dad would have to bring him to the house which we were living in and renovating without being registered. Two, if Jorge’s dad was working that day, Jorge might not be able to come and would be very upset. To mitigate these problems, I decided to grasp the nettle and go to the barracks and offer to pick Jorge up and bring him back from the party.

The Saturday before the fiesta, Rohan and I drove up to the barracks. The large arched olive doors of the building were locked shut, so I banged the iron door knocker. The small peep shutter slid open, and a face peered out at me through the metal grill.

“¿Que pasa?”

The following conversations were conducted in my pigeon Spanish.

“I would like to speak with Jorge”.

There was a grating of bolts, and one half of the door opened. The sergeant sat down behind his desk, I stood uneasily in front of him, Rohan seemed quite at home.

The sergeant rapidly wound the charging handle of a military field telephone and flipped one in a row of switches.

“Jorge, there is a foreigner to see you”.

While I waited, I studied the wanted posters on the cork-board; fortunately, my face wasn’t there, they were all ETA terrorists.

Shortly, the sergeant pointed a finger over my shoulder. A large green uniformed policeman descended the stairs eyeing me suspiciously.

“Oh, no,” I said, “I’m looking for little Jorge”.

The sergeant tutted, dismissed the man and rewound the field telephone flipping another switch.

“Juan, there’s a foreigner here, he wants to see Jorge”.

A smaller uniformed Guardia Civil came down the stairs with a young boy. While our two boys used the barracks as a playground, I explained my mission.

I told his father Jorge had been invited to Tayrne’s birthday party the following Saturday. I was worried he might be on duty and not be able to bring Jorge, so I would pick him up and bring him home. The father said it wouldn’t be a problem and that he would bring him.

Shit, so much for that cunning plan. There was nothing I could do now.

“OK” I bleated ” I’d better tell you where I live”.

The policeman gave me a wry smile.

“You don’t have to tell me where you live,” he said, “You live on the corner in Son Barcelo where the building work is going on”.

He knew exactly where I lived, and why wouldn’t he. “Come on Rohan” I called “We will see Jorge at the party next Saturday”.

The following week, a green and white Guardia Civil Renault 4 drove into our field. A uniformed officer stepped out and from the passenger side emerged, Jorge dressed in a full Batman costume for Tayrne’s fancy dress party.

That was the start of a long friendship between family Butler and the family of Juan from the Guardia Civil.

I often wonder. Did a tourist driving on the Cas Concos road that day see a Guardia Civil Renault 4 with a uniformed officer and Batman sitting beside him turn into Son Barcelo and exclaim?

“DID YOU SEE THAT?”