Paradise Lost.

Paradise Lost.

In September 1954, my world extended from my front door to the west along Highfield Crescent to the two shops by the main road, and to the east as far as my Auntie Mary’s house at 12 Ridgeway Road. I hadn’t ventured up to the top street at that time. At the back of our house, we had a large garden on either side of which were the gardens of the other families in the street, each separated by a low diamond link wire fence. My dad, like most people in Brogborough, grew vegetables and flowers, his favourite flower was the hollyhock. At the bottom of the garden, there was a lane that ran the length of the back of our street, Highfield Crescent. Across the lane, directly at the bottom of our garden was an open grass playground with two sets of swings, two seesaws, and a slide. There was also a high vaulting bar on which I could climb, hang by my legs and look at the world upside down. The things in the playground were painted dark-green, the same colour as the doors, windows and drain pipes of the houses. Beyond the playground was a cornfield with a pathway through its centre, surprisingly called the middle path. This path led to a small brick bridge across a narrow ditch. From there, the path went on to the brick factory where my dad worked. However, that was a dangerous place and forbidden territory, for a while anyway.

That was the extent of my world, it might have seemed like a small empire, but at the age of five, it was a vast, fascinating place full of mystery. I spent hours laying on my stomach, looking into the grass at small plants, flowers and hundreds of different types of little creatures with lots of legs and antenna sticking out of their heads. These creatures were of all shapes and sizes with spots and stripes of different types and colours. They scurried about their business, some in great gangs attacking lonesome wanderers, overpowering them and dragging their bodies into holes in the earth. Great life and death struggles went on every day. When I asked my dad about these things, he said they were insects, but if I looked really hard, I might find some fairies, unless they’d all gone to live in Ireland where there were plenty of the little people. I learnt the names of some of those small animals and spent my time chasing after butterflies and bees to see what they got up to. I also found the hiding places of lizards, frogs, toads, field mice and voles.

One of my favourite pastimes was laying on my back in the grass amongst the wild sweet peas and insects. Stuck to the earth with my arms outstretched, I wondered why I didn’t fall down into the clouds. In the clouds I saw, dragons, knights on horseback, pirate ships, all sorts of things that went scurrying across the sky. I wondered what clouds were made of and if I could walk on them. I thought that one day I might go along with them to see where they went, but first I would have to learn to fly, the birds did it so it couldn’t be that difficult. Each morning I’d get out of bed have my breakfast and wander off in search of some new discovery. With a mind uncluttered everything was possible, enchanting, unexplained and needed to be explored. Communication with my parents usually started with the words what, when, why, where or how.

One day an old mongrel dog adopted me and followed me around until I took it home and pleaded with my dad to let it stay. After that, there was never a time in my childhood when I didn’t have a dog, which was invariably called Rex.

My dad used to smoke Old Holburn tobacco. On one occasion he threw a half-smoked rollup into the empty fire grate and went out of the room. I picked it up and sat in his armchair. Unfortunately, he came back and caught me puffing on the smouldering butt. I thought I was going to get into trouble, but instead, he rolled a new one lit it and gave it to me. He said if I wanted to smoke not to do it behind his back and made me smoke the whole thing down to the end. He didn’t think I’d do it, but I did. By the end I was retching, my eyes were stinging, and tears were streaming down my cheeks. I never touched another cigarette until I was eighteen years old.

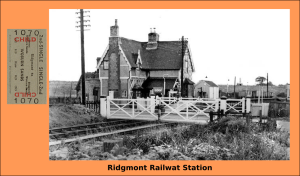

Sometimes I’d go with my parents down the middle path and over the brick bridge through the dangerous place to Ridgmont station to catch the train to Bedford. First, we had to go across the railway tracks to the station house. There in the waiting room was a little hatch in the wall where you bought your tickets, you paid your money, there were ‘chings’ as the date was stamped on each ticket before they were handed out through the hatch. My dad said you could pay for a ticket with unused postage stamps if you had some. With our tickets we would go back across the tracks and up the ramp onto the platform where passengers waited in an open-fronted shed with a long hard bench on the back wall. In this shelter I wondered about and annoyed the travellers with my questions all except for one older couple, the husband Mr Burgess never tired of my continual interrogation. Next to the station house was a fenced-off area full of great levers. Before the train came a man from the station house, dressed in a uniform and a peaked cap, came out and opened the two great gates across the railway track and swung them over to stop the traffic. Each gate had a large metal handled key that came free when it was used to lock the gate. The man then took the two keys back to the levers, put them into a block and turned them, which allowed him to operate the long levers.

Further along the track, a large red signal plate with a white stripe on it would swing down from the horizontal to a sloping angle to tell the train driver it was safe to pass. A little later a monstrous black steam-engine, belching smoke and hissing white steam with the driver leaning out of the cab would arrive hauling a string of coaches. We’d get on the train and go chugging off through the countryside passing the many brick factories that were built along the side of the track on the way to Bedford.

It was an idyllic, carefree existence, but unbeknown to me it was coming to an end. One day my mother sat me down and told me I would soon be going to school. Every day for the last year, my sister, Ellen, had gone off early each morning during the week and not come home until well after lunchtime. She told me she spent her day at school, learning to read and write and count with numbers. She said the children were let out for short periods called play-time, but then they had to go back into the building. It didn’t sound very nice to me, and I told my mum I didn’t want to go, but my mum said I had to go. When the fateful day arrived, a blue Horseshoe Company bus came to take us the two miles and up the hill to Ridgmont. When I got back home that evening, my mum asked how school had been. I told her it was alright, but I didn’t think I’d bother going back. That didn’t go down well, and I had the first of my life’s rude awakenings. Thus, I lost my freedom and was sentenced to serve school-time. For the next five years, I was in the tender care of Miss Boswell, Miss Bolton and the not so tender care of Miss Busbee. The three old spinster schoolmistresses who taught at Ridgmont school.