Blessed are the peacemakers.

Belfast airport early one morning April 1981. My first visit, Bobby Sands is close to death.

This could be any other airport in the UK until the policeman steps out from the crowd. He is not your fresh-faced British Bobby; he’s a much larger individual, the bulky flack jacket and the Sterling 9mm submachine gun make him even more imposing. The face is set and serious. His head swivels stops, assesses, continues, as android like he scans the hall. Everything about him is mat and dark: his uniform, machine pistol, boots. Even the harp badge on his flat peaked cap is blacked out and unglossed. He is probably a good man, but for now, I will treat him with the same respect as I would a black desert scorpion.

Anywhere else I’d be ready to go; my attache case contains my work papers, one clean shirt, and a change of socks and underwear, this normally saves time but flying to Belfast no one is allowed to carry hand luggage. The luggage arrives, and we identify and collect our own. Each piece comes newly wrapped in its individually sealed polythene bag. I’m told that this is to prevent theft of property. However, I suspect that it is really so that an analyser probe can be poked in to sniff to see if anyone has been carrying explosives.

I get the case and like others walk around holding up a company brochure and wait to be recognised. Someone taps me on the shoulder, says my name and asks if I am for S.I.S. I confirm I am, wishing he hadn’t used those initials; you have to admit, these guys have a real gallows sense of humour. Outside the car park is full and I wince at the security implications, I’m uneasy, and I want to be out of this confined space. I see a man asleep at the wheel of his car, a paperback book on his chest, the engine is running. Once on the open road, I feel a little more relaxed, until the driver starts telling his horror stories about the troubles. I know what he is up to, all of them in the office know this is my first trip, it’s their way of putting me at ease; just for ‘the craic’.

We make our first contact with the British Army. The road is set with concrete blocks. The car is forced to slow and meander its way through this low maize. Down the road a soldier stands upright, a long 7.62mm self-loading rifle pulled tight into his shoulder, the barrel moves back and forth as it follows our car on its slow zigzag path. Fifty yards behind him is another soldier kneeling; he is also pointing a rifle at us. I wonder which one is aimed at me. Where are the others? There is something unusual about the standing soldier; his helmet is the type used by tank commanders, wider at the sides and with earphones. He is talking into a thin, tube microphone that extends from under his helmet to his mouth. Like an armed telephonist, he is reading off the number plate of the car. By the time we pass the last block, we have been given clearance. He points the rifle skywards and waves us through. His colleague continues to cover the car as it passes down the road. Welcome to the UK!

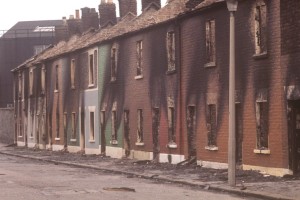

We drive along the hill road and look down onto Belfast. From here it looks like a score of other industrial cities, but as we drive down onto the streets the reality shows, there is an eeriness about the place. In the rows of terraced buildings, there is something strange and different. In places, the side of a building is completely exposed. For fifty or sixty yards, in some cases more, the area between one building and the next has been cleared of rubble, occasionally the rubble is still in place. I imagine someone who has just had a fight and now has half of his teeth missing. It’s a sinister smile to be greeted with. Shops, pubs and hotels are all screened with iron frames clad with steel mesh. Entrances to these places have gates made from the same material. The buildings are cages, like places under siege.

We arrived at the offices of Stewart Industrial Services. I am taken upstairs and offered a coffee and wait for the managing director. I peer down onto the street; it has started to rain. Two R.U.C, police officers, armed with sub-machine guns, are walking back to back, along the street. Like Siamese twins in flack jackets, one looking forward the other back, they make a slow patrol along the road. I feel vulnerable, as if I shouldn’t be watching them from this vantage point, so I step back from the window until they pass. A girl, in her early twenties, comes into the room with the coffee. She is from New Zealand, and I ask her what in heavens name she is doing in a town like this. She tells me that it is not so bad when you get used to it; in fact, she loves the place and the people.

The MD arrives, a large, jovial man with a strong Ulster accent and a nose spread across his face like a rugby player. After a brief talk about the radiation test facility we are going quote for, we leave for Davidson’s Engineering works. In the car park, the MD welcomes me to Belfast and offers me a seat in a beat up old Chrysler.

The security man opens the mesh gates, and we drive out, two suits, in a wreak of a car; who are we kidding? The gate clanks shut behind us. As we drive through the battered streets, the MD becomes serious. He explains that our route passes through some republican areas and if we get stopped I should keep my mouth shut, he will do the talking; my accent could get us into a lot of trouble.

Wonderful, born in the UK of a Southern Irish, Catholic, family with an English accent, I am in a no-win situation, I become mute. Many people don’t realise the fine dividing lines that exist between the opposing sides in Belfast. In places, it’s the difference between one side of a street to the other. From pavement to pavement there is a chasm of total ideological difference. At one point in our journey, on one side of the street, painted on a wall is an Irish Tricolour under which is written.

‘Support the Republican boys in their fight for freedom.’

On the other side of the street, a Union Jack is painted under which is written.

‘Bobby Sands. Slimmer of the year.’

A sensation runs down my spine as if the area is charged with electricity and I realised how close this place is to destruction.

The meeting at Davidsons is finished. On the way back to the office we feel a dull thud. What happens next probably lasts only 30 seconds, but it all seems to occur in slow motion. As we come around a corner, two cars are stopped in front of us. A pub, ‘The Elbow Room’ has just been bombed. It was probably not a big bomb as the main structure of the building is still intact. The doors and windows are blown out, and flames are pouring from the openings, blackening the walls. A few people are standing over something laying on the street. A drab, military green, armoured personnel carrier pulls out from a side street and stops, blocking off the road ahead. The back doors open and about ten British soldiers jump out and deploy across the street. One of the soldiers, either having forgotten or not having had time to do up his chin strap loses his helmet. The helmet falls off and tumbles across the road. The soldier, no more than eighteen, recovers the helmet and goes about his business.

The MD curses. He has a busy enough schedule today without this. He swings the wheel hard over, steps on the accelerator and with tyres screeching and burning smoke, the car shoots down a side alley. With his intimate knowledge of the back streets, we are soon back at the office.

In the office, they ask how it went, and before I can speak the MD says that everything went well and that we have a high probability of getting the order. To him, it’s just another working day.

I get dropped off at the airport for the evening flight back to London. There are no night flights out of Belfast now. By dark, the runways will be clear, with all planes on their way back to their home bases. That was my first experience of Belfast.