A day out in England with an America friend.

This occurred 35 years ago, so to avoid age-related memory dysfunction, before writing, I decided to check some details on the internet. However, lack of ‘link click’ discipline, funnelled me into a rabbit warren and a line of enquiry that led to, the ‘special relationship’ and World War II animosities between the British and Americans.

I was surprised that many opinions I’d heard on the subject were distorted or just wrong. No controversy intended, just information I found before telling the story.

The British narrative goes like this:

‘America came into World War II late. When it was over, they paid the Germans and gave Britain the bill’.

The American version goes:

‘America saved Britain’s ass by winning a war, not of America’s making’.

Neither perspective is entirely accurate.

The British say, when the Americans entered the war in December 1941, the tide had already turned. The Battle of Britain was won, Bletchley Park had broken Enigma, and Hitler had made the mistake of invading Russia. Arguably the defeat of Germany was inevitable. When the Americans landed in North Africa on 8 Nov 1942, the Battle of El Alamein was already over, and Rommel’s Africa Korps was in retreat.

To this, the American say had they not come into the war it would have dragged on. Possibly resulting in Europe becoming part of the Soviet Union. Alternatively, had Germany developed an atomic bomb for its V2 rocket, Britain would have been forced to surrender.

For me, there’s no doubt, America’s entry altered both the course and the duration of the war.

Now, to the money.

Most British believe America paid Germany after the war and Britain got the bill. That is a myth. Germany received $510 million from the Marshal Plan, but Britain received $1,316 million. The problem was, Britain used the money to maintain the Empire instead of modernising its industries.

After 1941, under ‘Lend-Lease’, Britain wasn’t required to pay for materials received from America for the war effort. The sum repaid on 29 Dec 2006 was for a $4.34 billion, 2% annual interest, Post War loan from America, to cover Britain’s foreign debts to avert bankruptcy.

And strangely, on 9 Mar 2015, Britain finally repaid another £1.9billion debt for loans, mainly from America, to finance the 1914-18 First World War. Another complicated story.

So, on with the story:

I was sitting at home in Flitwick when the telephone rang. I picked it up and received a tirade of verbal abuse in a Texas accent.

‘Greg McDaniel,’ I said ‘Where are you?’

‘I’m in the Holiday Inn, Gatwick Airport, you son of a bitch.’ Greg was renowned for his terms of endearment.

‘How long are you here for?’

‘Three days.’

‘OK, I’ll be there in a couple of hours to pick you up. You’ll stay with us.’

Greg was in transit from Japan to Texas. Head of Radiotherapy at the Dallas Pentecostal Hospital, he was returning home from Japan. He had been entrusted with the purchase of a 4 mega Volt, multi-million dollar, linear accelerator for cancer treatment.

Greg and I had met a few years earlier in Atlanta, Georgia. I’d been setting up a manufacturing facility for High Definition X-Ray equipment for an American company. He was my counterpart in that company, and we worked together to exchange technical information. He was everything a Texan should be, six foot two, loud and brash. We immediately became the best of friends. Most of my evenings in Georgia were spent at Greg’s house laying shoe-less on the floor, with George and Kelly his young children. I had the intricacies of American football explained to me in infinite detail. To this day, I still do not understand any of it. Robin, his wife, would cook the most outrageously large meals to sustain me. So generally speaking, I felt quite at home.

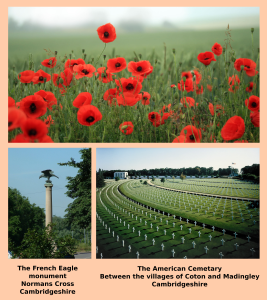

I left for Gatwick and brought Greg back to stay with us. I stopped off at a country pub to allow him to sample a pint of real British ale from the wood. He was not impressed, however, as we talked, I discovered that he was a steam engine enthusiast, something I hadn’t known. The next day Sandy found out, from our friend Dawn, that there was an old railway museum fifty miles north up the A1. The Nene Valley Railway museum. The following morning Greg and I left early and drove off to see the engines. Halfway to our destination, we passed a monument, a tall column on top of which was a large eagle. I’d passed this monument on numerous occasions as I’d travelled north to work in Glasgow and Aberdeen, but I had never stopped to see what it was. I’d assumed that it was put up for American airmen killed in the Second World War. There were many U.S. air bases around Cambridge. We stopped and read the plaque at the bottom of the column. To our surprise, it was nothing to do with World War II. The monument had been erected in commemoration of French soldiers and sailors from the Napoleonic wars who had died in the Norman Cross prisoner of war camp between 1797 and 1814. The French prisoners had obviously made a good impression on the locals. We drove off astonished that an English society should raise the money to build a monument to foreign prisoners of war.

We found the railway museum and Greg took lots of photographs. Some of them were taken by me perched on his shoulders so that he could get the creative view that he wanted.

On the way back home two A10 Thunderbolt (Wart Hog) tank busters flew over us. I recounted to Greg a story I’d heard about a senator who had once visited England to inspect the American airbases. After a tour of a few bases, he pulled a base commander over, expressed his admiration at the impressive facilities and then asked tentatively how much it all cost. The senator was mystified when the commander replied that the bases cost nothing.

‘What! You mean the Brits let us have all this for nothing. We pay millions for the Philippines.’

‘Yes sir, they let us have it for nothing.’

The two of us didn’t know much about why there was no cost for the bases and didn’t really think much more about it. As we drove on towards Bedford on the A1, I remembered the American war cemetery outside Cambridge. This was another thing I had passed on the way to work somewhere and never taken the time to stop and look. I asked Greg if he would like to go there. He said he would, and so we turned off the main road and headed for Cambridge. It was one of those special English days, no clouds, no swirling mist, just blue sky, sunshine and green, green, green.

We found our way to the cemetery and parked. I will never ever forget that day. The two of us walked through the entrance gate. Two people from very different cultures. He, a giant of a man and me standing like a child beside him. We looked down on the orderly, semi-circular rows of white crosses that stretched before us. Row upon row of them on a neatly clipped carpet of green grass overlooking peaceful English countryside. Nothing was said, but when we finally looked at each other, we were both crying.The cemetery has the remains of 3,812 war dead from every state of the Union. The Wall of the Missing displays 5,127 names of those whose bodies were never recovered. It is the only permanent World War II American Military Cemetery in the United Kingdom.

Kemal Atatürk, died 81 years ago (10 Nov 1938) on this coming Remembrance Sunday.

Poignantly, in a speech he made after the Turkish army defeated the Allied forces at Gallipoli in 1915, referring to both his own soldiers (Mehmets) and those of the enemy (Johnnies ), he said:

“Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives … You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side here in this country of ours … You, the mothers who sent their sons from

faraway countries, wipe away your tears; your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well.”