José El inglés

José El inglés

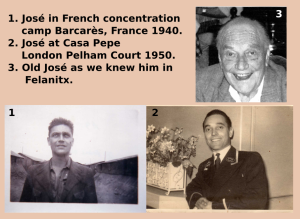

In the summer of 1986, during our first year living on the island of Mallorca, Sandy was at the Felanitx Sunday market, standing on the steps of the church with our two children. She was approached by a small, slim man in a light suit who asked her if she was English. She replied, “Yes”.

“Oh, I love the English,” he said, and that is how our friendship with José Ferrer Marruguat began.

José was a generous, stubborn, complicated old man, and a good friend for as long as we lived in Mallorca, until his death on 3 December 2008.

If he’d lived until 24 May 2009, we would have had a street party in Felanitx to celebrate his one-hundredth birthday, but that wasn’t to be.

I could tell many stories about José’s life, he never passed up an opportunity to let you know of his exploits. I could recite the stories in my head as he was telling them, I had heard them so many times. However, I am eternally grateful to him for those memories, insight into a time long gone.

Before I continue, I should explain how this Mallorquín became such an Anglophile, and why he was known in Felanitx as ‘El inglés’, the Englishman.

On 1 April 1939, the Spanish Civil War came to an end with the rebel Franco’s Nationalist victory over the Government forces. José was a young captain in the Army of the Republic, he and his men were holed-up in an ice-covered cave high in the Pyrenees. They didn’t know it, but the war was already over when they ran out of supplies and decided to fight their way out. They escaped across the border into France, where they were interned, put into a concentration camp and moved around the country as forced labour. A year later, José was in Brest building coastal defences. France was about to fall and Operation Dynamo, the evacuation from Dunkirk, was underway. As a Spanish Republican officer, José would have been shot if he had been captured by the Germans.

Here I will continue in José’s own words:

“There was a ship at the dock-side, the French guard would not let me on board because I was Spanish. A little later, a drunken French sailor, returning from town, fell between the ship and the wharf. The guard left his post to help the sailor, and in the confusion, I got onto the ship. I hid in a hold and spent the night bumping into people in the dark. After the ship sailed we were discovered, there were forty of us. We were lined up, and they tried to press us into joining the Foreign Legion, who were en-route to Djibouti. No one signed up, we told them they could keep their war, we’d already had ours.

The ship had to pull into Southampton, but the French were determined to take us to Africa, to stop us from escaping they put us in a cage and hoisted it up on a derrick.

In Southampton, a port official came on board and asked who the men in the cage were. The French captain said it was a French boat, and it was none of his business. We shouted down that we were Spanish. The official agreed that it was a French boat, but we were Spanish, and it was in a British port. He said the ship was going nowhere until he found out the legal position and left. An hour later, he returned and ordered the captain to lower the cage and let us out. He asked us if we wanted to get off in England or go on to Djibouti. We all wanted to stay in England. He took us off the ship, called over a British Bobby, who was on the dock and asked him to look after us until he found out what to do with us.

When he’d gone, the policeman told us all to sit down. The strange thing was, we did as we were told, and he didn’t even have a gun. After an hour, the official hadn’t returned, so the policeman asked us to get up and go with him. We followed him to the Town Hall, where we were given tea and sandwiches. After a while the official found us, he took us to the railway station and put us unaccompanied onto a train to London. He told us not to get off the train until we reached Waterloo station, where someone would be waiting. We arrived in London and were taken to Alexandra Palace where food and accommodation had been arranged for us.

We were foreign aliens, but we were treated with dignity, and this, while Britain was in crisis attempting to evacuate her troops and the French from Dunkirk.

After two months, we had a visit from the MI5. When they were satisfied, I had been a captain in the Army of the Republic, they said they had a job for me; I started training the Home Guard. One evening I was walking home from work, there were men in a trench putting up reinforcing steel for an air-raid shelter. I stopped to watch and told them they were doing it wrong. The manager came over and asked what the bloody foreigner had said, I told him. He asked how I knew it was wrong. I said I’d been bombed by bloody foreigners, and jumped into the trench to show him the right way to do it. Now, I had two jobs”.

Because of his knowledge of wines and spirits, gained during his time living in Barcelona, José’s services were in demand in London’s post-war resurgent club and restaurant scene, where he mixed with the rich and famous. With Franco firmly in control in Spain, it wasn’t safe for José to return home, so he stayed on in England. José met and married an Irish girl Bridget, and they had two sons. A friend high up in Scotland Yard vouched for José, he became a British citizen and was issued with a passport. That passport became his most precious possession.

In November 1975 Franco died. At the end of December 1978, the new Constitution came into force, and modern Spain was born. At this time José’s two sons were grown up with their own families. José had fallen out with his youngest son and relations with his wife had become difficult. One morning in the autumn of 1982, José packed a suitcase, took a ferry to France, a train to Barcelona and from there a ferry to Palma de Mallorca. From Palma, he took a bus the 60 Km to Felanitx, the place of his birth.

Here again, I will continue in José’s own words:

“I sat in the back of the bus, we drove from town to town. At one point we stopped, people got off, and I was the only person left on the bus. I sat there waiting, the driver came to the back and told me I had to get off the bus. I told him I was staying on the bus because I was going to Felanitx.

‘This is Felanitx’ he replied.

I hadn’t been to Felanitx since I left as a young man with my mother, to go and live in Barcelona after my father died. I didn’t recognise the place.

I stood in the palm square, Plaza España, which had been a field outside of the town with a water trough for horses when I was a boy. I walked across the square to the Tobacco shop and turned the corner going up towards the church. I came face to face with an old man. We stood looking at each other, and then he said.

‘Way-up, Pepe, where have you been?’ as if he had only seen me yesterday.

It was my old school friend Toni Estepol, who I hadn’t seen for fifty years. Pepe was my nick-name at school”.

Toni took José home and looked after him until he found himself a little apartment near the Plaza Paz. José settled back into life in Felanitx. Every day he would rise, put on a suit and tie and walk into town and reestablish old relationships. A Felanitx boy by birth, he now became known locally as ‘El inglés’, the Englishman, and I can tell you he never let anyone forget it.

For José, England was the greatest country on earth, even though, over the years he began to think it was letting down its standards. Every day he went to pick up his copy of the Daily Mirror, a UK tabloid, which he had delivered by special order to the newspaper shop.

And so, if you’re ever in Felanitx for the Sunday market, and you think it is just an old Mallorcan town and these are ordinary island folk, then think again! There are not many ordinary Mallorquínas, believe me, I know.