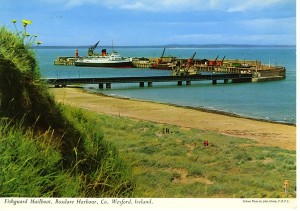

Memories of Rosslare Harbour.

People consider me to be English because that’s where I was born. However, in my formative years, until I left school, every year I spent my summer holidays in Ireland, and the strangest thing is that my first childhood memory is of waking up in a brass framed bed in granddad Boyce’s house at 1170 Colville Street, Rosslare Harbour, with a vague memory of a long journey by train and ship. That memory is as clear now as it was then, the chatter of jackdaws in the plantation behind the house, and the smell of fresh sea fish frying on a paraffin primus stove.

Early in the mornings, once I was big enough to roam the village by myself, I would go down to the harbour and wait for my uncle Ben’s boat to come in from the nights fishing. After the crew had offloaded the boxes to go onto the Dublin train, I would help uncle Ben bring his share of the catch home. We might have plaice, turbot, sole, dabs, sea bass and sometimes great crabs and the occasional black lobster. The two of us would climb the ninety-nine steps to the top of the cliff, the wire holding the hank of fish through their gills would be by then cutting into my hand, but I wouldn’t accept any help in carrying my prize home. A little way on from the clifftop, on the left side of the road, was a building with barely legible big faded letters declaring ‘Boyce’s Tea Rooms’. This was a remnant from my great-grandfather’s time. He was a Scottish civil engineer, who had come to Rosslare around 1904 to work on the pier extension and he never went home. The harbour storm wall was still known as Boyce’s Wall. Back at Colville street, we would fry up the fish and, if we had them, drop the crabs or lobster into boiling water. The family would then settle down to breakfast.

Funnily enough, my auntie Mae had a cafe, ‘The Butler Arms’, and a petrol station on the clifftop where the Dublin road came up from the harbour. Granddad Butler had been a soldier in the British Army in World War I, he survived the Gallipoli campaign in Turkey only to be blinded at Passchendaele. He moved from Rathfadden, in the city of Waterford, to Rosslare in the early 1950s. It’s quite bizarre to think that if he had been killed on the Western Front, I would not be sitting here now writing this, and neither myself, my cousins, nor my children and grandchildren would exist today.

Most times, when my mum took me to see friends and relations in Rosslare, I would be given at least a silver sixpence or shilling. However, I loved it best when she took me to see an old lady called Mrs Doran. Every time I saw this lady, she gave me a silver half-crown coin; two shillings and sixpence was good money for a child in those days. I would roam the beaches all day long, going south to Carnsore Point, seven miles of empty sands with waves crashing on the shore and reverberating against the cliffs. Or I’d go north to the rock pools, full of small crabs, shrimp, crustacean and other strange creatures. Then, I’d take the clifftop to Rosslare Strand. That’s where Commodore John Barry, “The Father of the American Navy”, grew up with his uncle Nicholas, a fisherman after his family was evicted from their home in Tacumshane by the British. Rosslare Strand was also where Guglielmo Marconi built his repeater station when he transmitted the first radio signal from England across the Atlantic in 1901. Marconi’s mother was Annie Jameson from Wexford, about 10 kilometres away. Annie was the granddaughter of John Jameson, the founder of the Jameson Irish Whiskey Company. Of course, that meant nothing to me then. All I was interested in was going off with my friend Terrance O’Brien who lived in Goulding street near the ball alley where we played handball, like squash, but without a racket. We were always up to mischief down on the harbour dock. We’d collect the small mixer drink bottles that were discarded on the track from the Dublin express dining cars and take them up to Coady’s store to collect the deposit money. I never figured out why the passengers dropped the bottles onto the track, but it was a good little business for us.

Best of all, when Cadbury shipped sacks of chocolate crumb, which looked like brown coal coke, to their Dublin factory, that would inspire a raid to try to spike the hessian sacks on the dock and fill our pockets. If caught by employees of the railway company during these many nefarious activities, we’d be reprimanded.

“Terrance O’Brien and that brigand with ya, feck off home before I tell ya mother”, and we’d lope off laughing with our ill-gotten gains.

There used to be a cinema in Rosslare at that time, a small building on St Martin’s Road if I remember correctly. The seats and the projector were all in the same room. The local boys and girls would congregate together, and when the lights went out, there would be a total uproar from the front rows. Every now and then the lights would go on, and the lady projectionist would rebuke us.

“I know what you’re up to at the front, settle down, or I’ll put you all out. You Terrance O’Brien and Winnie Boyce’s boy from England, behave yourselves or I’ll tell your mothers’. Funny thing in Ireland, it was always your mother you had to be afraid of. To this day I can’t remember one bit of the Paul Newman film ‘The Moving Target’.

After leaving school, I continued visiting Rosslare. Like a lot of others, Terrance had moved away for work, to London I think, this was long before the Gaelic Tiger economy of the mid-1990s. Then I spent more time in the Railway Club with uncle Ben or in Rosslare’s only hotel Hotel at that time drinking with my friend Brendan Walsh. Brendan was a volunteer RNLI lifeboatman, the son of RNLI Silver Medal holder Coxswain Richard Walsh. One day Brendan told me that a man from the RNLI in the UK had come to inform the crew about the new hi-tech lifeboat they were getting; the pièce de résistance of the boat was that it was self-righting if it capsized.

“And what do you think of that,” asked the Englishman.

“Well, I think I’d prefer one that didn’t turn over in the first place” was Brendan’s reply.

Another night, we were drinking in the hotel well after hours when suddenly the barman shouted.

“Everyone out, the Guarda are coming”.

Pints in hand, everyone made for the door. Not fully trained in the skill of rapid pub evacuation I was the last one out. The police car arrived to find fifteen men standing in a line on the clifftop, hands in pockets or smoking, taking the night air and enjoying the view of the harbour lights. A large officer walked down the line asking each man by name how his mother was or how are the fish running or some such thing until he got to me.

“And who are you?” he asked.

“He’s Bernard Boyce’s grandson” the man beside me answered.

“Can’t he speak?”.

“He’s English” as if that explained everything.

The Guarda lowered his head and said into my ear.

“Where’s the drink?”. I said nothing, the Guarda continued.

“Give us a sup of ya beer and I’ll say nothing about this”. He knew how to break a man.

I reached down behind the low wall in front of me and brought up an almost full pint of Smithwicks. The Guarda took it, drunk it and handed me the empty glass.

“Regards to ya granddaddy,” he said, and then “Grand night lads”, and walked back to the car and drove off.

When he had gone, I asked one of the men how the barman had known he was coming.

“The Desk Sergent telephoned him,” he said.

That’s all from Rosslare harbour for now.