How we came to buy a vineyard (Part 1)

How we came to buy a vineyard (Part 1)

Transforming Cana Cavea from a ruin into a home was hard work. We put in an extravagant six by twelve-metre swimming pool and Jacuzzi and established a natural rambling garden that occupied much of our time. We converted the donkey stable into an apartment with two bedrooms, kitchen, dining room and a bathroom. From this, we earned a modest income from romantics looking for an alternative Mediterranean experience. We had a good water supply and a not so good electricity supply. For years the lights dimmed whenever we put on the electric kettle.

We were accepted into the village of Son Barcelo who referred to us, not as foreigners, but as ‘the young ones’. Our Cana Cavea was a home with a soul.

Once Spain was in the EEC, new houses went up at a pace. Derelict properties were bought and converted into opulent holiday homes. In just a few years our neighbourhood morphed into Beverly Hills. Prices of old farmhouses and land increased tenfold, and material and labour cost rose. The area between Es Carritxo and S’horta became known locally as Hamburger Valley after a proliferation of inhabitants from that city in Germany.

The Ajuntamento (Town Hall) reeled under the surge. Before the northern invasion, there was an understanding with the Ajuntamento. If you modified your property and it wasn’t too grandiose, nothing was said. If the Ajuntamento thought you’d overstepped the mark you’d be fined. Fines were moderate and covered building permissions for the work done. They were less than architects’ fees, and it kept paperwork to a minimum. People kept within acceptable boundaries in a self-regulating anarchy. The Ajuntamento would get cranky if a property was built without planning permission, but demolitions were uncommon. However, no escrituras (deeds) were issued, resulting in a nonregistered house that was unlikely to be sold unless the paperwork was first legalised. Generally, everything had been easy going and low key. In Mallorca, the problem was as big as you made it.

Many new arrivals treated Mallorca like mainland Spain. The most incongruous villas blossomed on the skylines. Barbed wire topped fences were erected, gates and private property signs went up, and public camino’s (lanes) were illegally closed off. The Ajuntamentos had to act to save the island and their own credibility. Regulations that had always been in place were brought out and dusted off. This, combined with new directives from Brussels, brought unwelcome change to our lives. The Earp brothers were on the streets of Mallorca, law and order had arrived, and I felt like a cowboy after the railroad had come through. My world was disappearing like the Amazon rain forest under the chainsaw. Still, we couldn’t complain, we had three years of Old Mallorca before that window in time closed.

This upheaval disrupted my life far more than it did the Mallocans. They seemed to cope with the change and still maintain their culture. Why shouldn’t they, over the years they have been invaded by Romans, Mores, Catalans, Spanish and more recently Tui, Thomson and Cosmos. In the end, the invaders were assimilated or went home. In the shadow of powerful neighbours, Mallorcans are masters of the hidden agenda. They listen to the argument for change and then go on doing what works for them. They live and let live, adapt to things useful to them, hold on to their values, retain their identity and are very successful in what they do.

The Last Valley:

The upside in this change was that we had, some years earlier, invested in 38,000 square metres of beautiful land in a tranquil spot beneath the monastery of San Salvador. It reminded me of a film ‘The Last Valley’, that told the story of a hidden valley that escaped the turmoil of Europe’s Thirty Years War. So that’s what we called it.

As usual, this all came about by a series of happy accidents.

The main reasons we’d survived in Mallorca was due to Sandy’s talent for finding and selling property. This came about by chance when a local farmer asked her to sell an old ruin. In those days, farmers did not sell often, and it was generally for a specific reason such as a wedding, to build or buy a house for a child. On not so rare occasions a farmer sold to pay off a gambling debt. On this occasion the farmer wanted the money to send his daughter to university on the mainland to study Industrial Engineering. Sandy quickly sold the property to an Irish builder from London called Jerry.

Mallorcans weren’t enthusiastic about paying income tax, considering the Hacienda (tax office) to be a lot of corrupt robbers. It probably costs more in time and effort concocting their schemes for avoidance than if they’d just paid the tax, but for them, it was a matter of honour to stop the state getting its hands on their cash. Farmers conducted their business with discretion. Using an estate agent’s office was not customary, transactions were carried out by word of mouth through a network. Sandy became part of that network and operated under the sobriquet ‘La Rubia’ (the blonde). Sandy had a good working relationship with a man named Juan. To save confusion as to which Juan we are talking about I will refer to him as Estate Agent Juan. The list of prefixed Juan’s will increase as my stories proceed, Juan is a popular name.

Estate Agent Juan was in his late fifties, medium height and a little rotund with a balding head. He ran his business from a bar in the Palm Square in Felanitx. Between eight and ten each morning the bar filled with workers, farmers, police and other personalities who came in for coffee and brandy. Then, you would find Juan holding court if you could locate him in the din and the smog from black tobacco and acrid cigars. The bar was ideal for conducting delicate transactions. Covert eavesdropping was impossible, it was difficult enough to hear the person sitting next to you. However, Juan had an acutely tuned ear for a deal or a profit. There wasn’t much that happened in the property business that Juan didn’t know about. If you had a client with a particular requirement, then Juan was your man.

Sandy often met Juan in the bar, and he would arrange an outing to show her what was for sale. Some of the properties weren’t that interesting, and I got the impression that he just liked driving around the place with a young foreign blonde who just happened to be my wife.

Here I wander to introduce you to one of Juan’s and his wife’s little idiosyncrasies. They were both animal lovers to the extent of obsession. Juan collected dogs, his wife Katty collected cats. I don’t mean a dozen or so, no, they had colonies. Juan had a sanctuary outside Felanitx with over a hundred skinny looking Ibisenco hunting dogs, they’ weren’t underfed, it’s a characteristic of the breed. He had rows of concrete roofed kennels with large exercise paddocks. It must cost him a fortune to care for them.

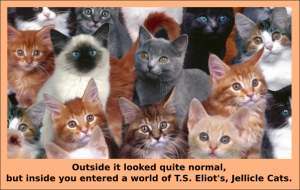

All this paled into insignificance compared to the large house with its high walled garden his wife had in Felanitx. She didn’t live there it was kept exclusively for cats. I went one day with Sandy and Katty for reasons forgotten. Outside it looked quite normal, but inside you entered a world of T.S. Eliot’s, Jellicle Cats. The courtyard was carpeted with them, and inside they were wall to wall.

Cats resided on chairs, on tables, under tables, on top and in cupboards, in the kitchen sink and on the drainer. The place was dripping with cats, brown, black, white, grey and tabby ones. There were Persians, Siamese, Manx, types I didn’t know. Mature cats, young cats, kittens and cat equivalents of Chelsea pensioners that stumbled around in their twilight years. They lay in the sun waiting to be fed, groomed, stroked and talked to. Walking around was like treading a mine-field. One wrong step brought a disgruntled shriek resulting in startled flight or a lacerated leg dependent on the feline character involved.