The giant Forties Field, east of Aberdeen, was discovered in 1970. However, a savage environment and high costs limited the viability of North Sea oil. All that changed when prices quadrupled in the 1973 oil crisis. A frenzy of land and sub-sea pipeline construction followed to retrieve the gas and oil. Every welded joint had to be inspected before those pipelines were buried or submerged under the sea.

One April morning in 1976, Scanray’s service department on the Water Eaton Industrial Estate, Bletchley was a scene of chaos. The place was stacked out with piles of damaged industrial X-Ray equipment. More suited to factories, the equipment was now operating on the front line of the North Sea’s oil boom.

I’d been employed as Scanray’s Engineering Manager from the 2nd of February. One of my primary jobs was to sort out that service chaos. I’d only just returned from a month at the parent company in Copenhagen Denmark learning how X-Ray equipment was made. In May, I was booked into a Practical Radiography residential course at The Welding Institute, Cambridge to understand how industrial X-Rays were used. To say I was green was an understatement.

Scanray’s sales director breezed in, a big blond chap, typical ‘can do’ sales type. He said, “There’s a problem with Santa Fe. If one more X-Ray set goes down, they’ll have to stop laying pipe. You need to get a service engineer up there pronto.”

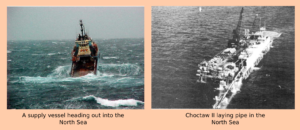

The American company, Santa Fe International Corp, was operating a pipe-laying barge, named Choctaw II, in the Forties field. In those days, a North Sea lay barge cost around $200,000 a day to run. Any company that stopped the barge from laying pipe was liable to pick up the bill.

As if I had nothing else to do, the sales director finished with, “You should go up with him and see how the equipment’s used.”

Later, when I was more established in the company, I asked him while we returned from a meeting with clients. “That equipment you just sold them, is it’s ours? Because I don’t know anything, we’ve got that does what you said?”

But at that time, new to the job, I couldn’t help but be intimidated.

That afternoon Ken Day the service engineer and I were on a British Airways Trident Shuttle from Heathrow to Aberdeen. We had a toolkit, a bag of spares, and a change of clothes.

Aberdeen airport was buzzing with oilmen and rig workers going on and off shift. There were enough six-foot-plus loud Americans in stetsons and cowboy boots to make you think you’d landed in Texas. We pushed our way through the crowd and found a man holding up a ‘BIX for Scanray’ sign. British Industrial X-Ray, were the end-users of the equipment. They were not happy. Soon we were driving at speed the 36 miles to Peterhead.

It was dark when we arrived at Peterhead Port Authority. After some paperwork formalities, we were taken to the supply vessel that would ferry us to the lay barge. It wasn’t big as ships go. The superstructure and bridge were situated forward. The aft end, a long open flat deck for the transportation of lengths of pipe and other cargo, was empty. Positioned at regular intervals above the water-line along the vessel’s side, were enormous tractor tyres that acted as fenders. The boat’s inside was cramped. There was a galley where about eight of us passengers congregated. The galley had a large table with benches fixed to the floor, around which we all sat in discomfort. After an hour or so, we were served mugs of stewed tea and corned beef sandwiches by a surly Scot. Rough as conditions were, the tea and sandwiches were appreciated after a day with little time to stop for food. Some of the group were regulars and spent their time smoking and playing cards. I got into a conversation with the tall northerner next to me who turned out to be a crane driver going back on shift. Before midnight, the ship vibrated as its engines came to life and we manoeuvred from the harbour into the North Sea. The further we travelled into the open sea, the worse became the weather. The ship pitched and rolled as it ploughed through rising waves. I continued talking with the crane driver. Then, finally exhausted, despite the battering of the sea, I fell asleep with my head on my arms on the table.

About 04:00, I was nudged by the crane driver. “We’ll be getting off soon”.

Ken and I gathered our gear and assembled on the aft deck with the others.

The lay barge was ablaze with spotlights that reflected across the black waves. As we closed, clanking and banging drifted over the boiling waters above the noise of the storm from the floating ant-hill working 24 hours a day.

Choctaw II, was unlike any ship I’d ever seen. It was like a long rectangular aircraft carrier. One side of its flat deck was cluttered with pipes, machinery, and storage cabins and was dominated by a gigantic crane. On the other side, its whole length was a covered multi-stage welding bay. From this structure, as each weld was completed, the pipe inched its way out and down into the sea. The laying process was controlled from the bridge that rose from the other end of the welding bay. Behind the bridge, was a helipad the width of the barge.

Our captain manoeuvred alongside trying to keep a safe distance from the other vessel. Still, the storm slammed us against the massive barge. Each time it did so, there was a thud of tractor tyre fenders against the hull. The deck pitched up ten feet with the waves, and we were saturated with spray.

“How the hell are we getting off?” I shouted to the crane diver”. He pointed skyward.

High above us, Choctaw’s crane swung out, a transfer basket hanging by a cable from its jib. The basket’s base was a large padded ring with a canvas floor. Connected to this ring were four equally spaced short rope ladders that rose up to a smaller top-ring to form a cone. The basket crumpled as the deck rose up and hit it. Then a dance started between the crane and the supply vessel. In a graceful waltz, the crane driver kept a two-foot gap between the basket and the rising and falling deck.

One of the old hands ran across the pitching deck. He threw his gear into the basket, jumped and hung on to the outside of the cone. With his feet dangling, the basket shot into the air trailing away at an angle as the jib rotated back to the barge. The dance restarted and the next man ran forward.

The crane driver by my side shouted above the howling wind.

“If the basket collapses and the rope fouls, leave it. Don’t get tangled in it. Wait.”

Then, with a wry smile, before he ran across the deck, he shouted. “When you’re on board, remember, NEVER UPSET THE CRANE DRIVER”.

Then it was my turn. ‘Fuck!’ I thought ‘This wasn’t in my training schedule’.

That transfer was probably the most terrifying thing I’ve ever done. Just as well, I didn’t know it was going to happen that way.

After that, everything was an anticlimax. Fighting for a sheltered place to work among the other maintenance crews on the open deck. Lack of sleep and ‘Hot racking’, being allocated a bunk just vacated by a worker going on shift. An hour later, being ousted by another indignant worker returning from shift who had priority for the bunk. Even being relegated to Ken’s assistant because I knew just enough about the equipment to be dangerous. None of this compared to a crane transfer between vessels at night in a storm.

Then it was time to go. Another night, another storm, but the weather was worse. They tried lashing the vessels together, but a steel hawser stretched and snapped, ricocheting across the supply ship’s deck like an elastic band. If it had hit anyone, it would have cut them in half. So they returned to letting the vessels slam into each other. Fortunately, the great barge’s deck was stable, you could get a grip of the rope ladder before being catapulted skyward.

I didn’t know who was in the crane towering over the deck, or even if they could recognise me. Non-the-less, I smiled and waved to the crane driver before I clung to the net.

Bloody salesman.