Here is an example of meticulous career planning on my part. In September 1966, as a Headleys Engineering Co Ltd apprentice, I was required to enroll with the engineering department of Dunstable College of Further Education for day release and evening classes. On enrollment day I was given two options. Option one was the City and Guilds craft course; Option 2 was the Technician’s course. As I already had GCE O Levels in Mathematics and Technical drawing, I was advised that my best option was the Technician’s course, it was also more prestigious than the craft course, so I enrolled. On the course start day, I presented myself at the engineering department and was sent to the main workshop. This place was full of lathes, milling machines and a number of work benches, each with a metalworking vice and an assortment of hand tools fixed to a vertical board, with the shape of each tool outlined and marked in red on a white background. The whole place smelled of mystic water-soluble cutting oil. After an introduction to the big power tools, we were subjected to a safety lecture where the instructor pointedly informed us “Remember! The day you cut your finger with one of these tools is the same day you almost lose your hand”. We were told that it was not recommended to turn on a lathe with the chuck key still in the chuck just to see how far it travelled across the workshop. We were told not to wear ties when working on the machines; it didn’t take much imagination to picture a tie being wrapped around the spindle of a whirling lathe and the owners head being dragged into the spinning chuck. Gross! It would be like the climax of a scene from the ‘Pit and the pendulum’ except much faster and without the high tension build up. Likewise, we were told to keep our shirt cuffs buttoned at all times and no hanging medallions or rings; these were all potential sources of decapitation, amputation and other types of mutilation.

Next, we had the horror stories about the misuse of pressurised air lines, the thin braided plastic tubes with trigger nozzles that hung down from the ceiling of the workshop. These tubes delivered 80 psi compressed air for cleaning metal shavings, cutting fluids and dust from the machines and workpieces. Air lines are found in every engineering factory and it is not uncommon to see apprentices, even experienced skilled workers, fooling around spraying each other with the compressed air or standing by their machines hosing themselves down to clean up before going off shift. It all looked pretty harmless; wrong, all this was not recommended. We were informed that compressed air in the mouth can rupture the lungs; directed into the navel, even through clothing, it can inflate and rupture the intestines. As little as 12 pounds pressure can blow an eye out of its socket or disintegrate an eardrum. On the skin, it can cause bubble embolisms in the blood stream resulting in coma, paralysis, heart failure and death. It can strip a body part of its flesh leaving naked bloody bone. In fact, it is used for exactly that purpose in meat processing factories. The list went on. Playfully spraying air up someone’s anus just didn’t bear thinking about. These innocuous tubes took on the appearance of green mambas hanging down waiting to ambush unsuspecting passing prey. The workshop was a primordial jungle full of countless unseen terrors. The most serious workshop peril and the one that would put us in most jeopardy was kept until last. The instructor strenuously emphasised that anyone caught fabricating metal discs the size of a sixpenny piece to fit the student union’s common room coffee machine, would be instantly expelled from the college.

Having been instilled with respect for our new environment, we were each assigned a work bench and given a rough cut lump of iron and a drawing of a rectangular block with the dimensions: seventy-five by fifty by twenty-five millimetres. We were told that using a file, a metal set square, a scribing tool, a micrometer and the vice only; we should produce a block to the dimensions shown on the drawing, with perfect right-angled sides and to a dimensional tolerance of zero point two of a millimetre. I started this task enthusiastically, but after fifteen minutes of trying to produce just one flat, straight-edged, right-angled corner, my enthusiasm began to wane. With time slipping away, iron filings mounting on the workbench like sands in an hourglass and the muscles in my arms beginning to ache, I wondered why I had ever considered becoming an engineer. The other techs were happily engaged in whittling away at their blocks, while I was thinking how I was going to make it through the next hour until the lesson ended. Was this a test of endurance? More likely the instructor wanted to know what he was letting himself in for with this new batch of Isambard Kingdom Brunel hopefuls. Either way, I wasn’t happy with my new career path. While I was descending, in my own mind, into a Slough of Despond, the door to the workshop opened and in walked a very officious looking man in a grey suit carrying a clipboard; he approached and spoke to the instructor who was standing close to the door on the other side of the workshop. I couldn’t hear what was being said over the rasping of files on metal, but I stopped my endeavours to observe this welcome distraction. The suit drew the instructor’s attention to something on the clipboard. The instructor, frowning slightly, read pensively scratching his chin with the tips of his fingers. After reading he scanned the room, presumably looking for whoever was shown on the paper. Eventually he pointed an accusing finger at me. I looked to my left and right, but to my dismay, I stood alone. The suit moved menacingly towards me, it seemed that I was responsible for some serious transgression. He stood in front of me and consulted the clipboard.

“Bernard James Butler” he inquired.

“Yes,” I replied sheepishly. Before I could ask what I was being accused of he continued.

“You failed O level Physics last year”. It was a damning statement, but I couldn’t deny it, and my best subject too.

“Yes, but I can explain”. I had no idea this was such a serious offense.

“Never mind that. You do have maths and tech drawing, don’t you?”.

“Yes”.

“Would you be prepared to do evening classes and retake physics?”.

“I would”. It seemed like the only response open to me.

“If that is the case, then you can join the ONC Engineering course today. Would you like to do that?”.

“Today, er yes” – anything to get out of this workshop and away from this block filing -.

“Then come with me”.

I put my work coat on the bench and picked up my satchel, the rasping stopped; the techs looked up as I was led away with the certain knowledge that the first coffee machine six penny piece filer had been apprehended.

I followed the grey suit out into the late morning sunshine. As we walked over to the main building the man explained to me the circumstances of my deliverance. The college was running a new trial Ordinary National Certificate engineering course. The new course would be an experiment, they were going to mix mechanical and electrical engineering subjects together. They believed that electronics was going to be the future and that mechanical engineers, who traditionally steered away from the mysteries of electricity, should prepare to meet that future. Unfortunately, the bulk of the mechanical engineers in the college did not share that view and they had only persuaded two volunteers to sign up for the course; three were needed to get the course approved. They were scraping the bottom of the barrel and I had been selected as the additional guinea pig. It was a dubious honour, but it was one I was prepared to accept.

We went to a classroom on the third floor of the main building. There were no desks in the room, just five lab-benches set out one behind the other. The benches had polished hardwood tops, approximately three feet wide and nine feet long, and were almost the width of the room; there was a three-foot clear walk-way on each side of the benches to allow the lecturer to prowl the room. Each bench had five equally spaced Bunsen burner gas outlets at their forward edge facing towards the podium and blackboard area at the front of the class. The bench tops were about three feet above floor level to allow students to stand while conducting experiments, and each bench had five high stools so that students could sit and write up their experimental results or take notes during lectures. My compliance with the man in grey must have been a foregone conclusion as the lesson was already underway. The other two volunteers were perched on stools on the front bench listening intently to the lecturer. The man in the grey suit made a brief introduction, told me to visit the front office after lunch to re-register on the ONC course, and excused himself. I nodded in recognition to the lecturer, who was obviously expecting me and took my place on a stool with the other two students. At the top of the blackboard, that took up most of the wall, was chalked: ‘Kirchhoff’s network theory’.

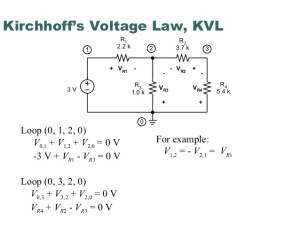

In the middle of the board was an electrical diagram showing an interconnected mesh of resistors and batteries, much more complicated than anything I had encountered in physics lessons.

Two statements had been written on the left of the diagram:

1. The total current flowing towards a junction is equal to the total current flowing away from that junction, that is to say, the algebraic sum of the currents flowing towards a junction is zero.

and

2. In a closed circuit the sum of the products of the currents and the resistance of each part of the circuit is equal to the resultant e.m.f. in the circuit.

On the right of the board, the lecturer was developing some simultaneous equations. My first reaction was blind panic, this looked like an impossible task. But then, something wonderful happened, almost a revelation. As I concentrated on the chalk strokes and the words, the elegance of what was being developed on the board became clear. The lecturer laid out a complex set of equations in logical numbered steps. As the answers began to emerge, I was captivated. I can’t explain what happened. It may have been a reaction to the mind-numbing boredom of block filing; of being in the room with two strangers and a teacher with no other distractions. Or, it might have been a confluence of what I had learned to date, a sort of enlightenment. Whatever the reason, fate had once again intervened on my behalf. I had a light bulb in the head moment, and from that day for the next four years, I would lead a double life. One life, the daily chore of working in a factory being prepared to operate as a cog in the system. The other, a mysterious world of Newton’s calculus and the secret life of the electron. My training as an engineering ninja had begun.

I re-registered for ONC: Mathematics, Applied Mechanics, Engineering Drawing and Electrical Engineering. I signed up for physics evening classes and over the next two years as well as mechanical engineering I learned about electromagnetic waves, Maxwell’s equations, the permeability of free space, dialectics, resonant frequency, cathode rays, diodes, valves and transistors.

My future looked good, but there was a dark cloud, of my own making, looming on my career horizon.