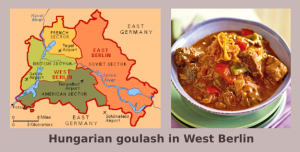

Hungarian goulash in West Berlin.

Hungarian goulash in West Berlin.

With the introduction of wide-bodied jets, like the 747 Jumbo, TriStar, and DC-10 at the beginning of the 1970s, mass transit air travel took off. From 1970 to 1980 the number of international air passengers doubled from 310 to 642 million. At the same time, aircraft hijackings quadrupled from 14 in the 1960s to 57 in the 1970s, more hijackings than any decade before or since.

To counter hijacking, Analytical Instruments in Cambridge was contracted by the British Airports Authority to make 19 passenger screening systems. The project, TRISCAN, included a walk-through metal detector, an explosives sniffer, and an X-Ray system. Scandinavian X-Ray UK (Scanray) was asked to supply the X-Ray equipment. This wasn’t too difficult a problem, you could shoot X-Rays through a case onto a phosphor screen; the screen would light up showing the case’s contents, you then used a low-light camera to send the phosphor’s image to a TV monitor; Scanray already did this for the ‘Bomb Squad’.

Detecting the odd hand grenade or Uzi 9mm machine pistol was important, but for this application, there was another vital consideration. The package holiday business was flourishing, and erasing passengers’ holiday snaps with an overdose of high energy X-Rays was not a Unique Selling Proposition, a new approach was required. The method adopted was to generate two X-Ray pulses one millisecond wide separated by a twenty-millisecond delay.

This had two benefits:

-it reduced the X-Rays to a level that would not overexpose film in a camera; and

-the pulses could be synchronised to the frame rate of a TV system.

Because humans have to see a picture for more than 150 milliseconds for it to register, the briefly generated image had to be stored; but in the 1970s RAM and video cards weren’t available. Therefore, a long delay phosphor device was required to save the image and re-write it to the TV screen. The only device available was from the American Huges Corporation, but there were problems.

-at 10,000 UK Pounds it was a fortune at that time;

-there was only one in the UK; and

-it was sensitive, protected US military technology.

Never-the-less, as it was for a UK Government security development, we received clearance and got our hands on one.

My role was first to build the electronics to test an X-Ray set to see if it was capable of generating the required radiation output. Once that was proven, I had to oversee the manufacture of the electronics, and the modification of the standard X-Ray equipment.

A few weeks into the development, I was in Scanray’s Danish factory in Hvidover just outside Copenhagen checking on the progress of nineteen 200Kv X-Ray sets for the project. The day was going well until the afternoon when Scanray UK telephoned. Development of the system had come to a halt, the Huges image store had failed and would have to go to the States for repair, the delay would jeopardise the project. Fortunately, there was one in Berlin owned by a Dr Warrikhoff who had agreed to loan it to us.

I asked if Warrikhoff was a German name. No, it was Hungarian. Hungary was part of the Eastern Block, aligned with the USSR. I wondered which part of Berlin I was going to, East or West. It turned out Dr Warrikhoff was ‘one of us’, he had an X-Ray laboratory in West Berlin and was probably funded by the Western Allies just to piss off the Russians. It was quite exciting really, going to meet a Hungarian scientist to pick up some sensitive US technology, it was all a bit James Bond.

Early next morning I was on a plane out of Copenhagen, en-route to West Berlin, with a ticket for a direct flight back to London that afternoon. I landed at Tempelhof airport at about 11am. Dr Harald Warrikhoff, a man probably in his early fifties, met me and we drove directly to his laboratory, an austere building on Lise Meitner Strasse.

His lab was a trove of bespoke X-Ray equipment. The devices ranged from the tiny, a few centimetres in diameter, to huge things in large glass jars with motor-driven rotating anodes. There were high voltage generators, vacuum pumps, oscilloscopes and test meters, all the elements needed to shoot electrons up evacuated tubes. It was like the set from some futuristic sci-fi movie. He worked with the Max-Planck-Society, which probably had a bearing on the name of the street; Lise Meitner, an overlooked Jewish woman scientist who fled Germany in 1938, she should have received the 1944 Nobel Prize for the discovery of nuclear fission with Otto Hahn.

Dr Warrikhoff brought me the Huges’ store, it was about 48x15x40 cm and heavy. I would have to carry it as hand luggage, keeping it with me at all times. As I had some time to spare, he kindly asked if I would like to see a bit of Berlin. I told him I would, but first I needed an invoice for hiring the Huges’ store. He said he didn’t want payment, and we could keep it until we finished our development.

“Is there something I can do for you then?” I asked.

He thought for a while before answering.

“There is a special plumbers tool that when you cut copper pipe, it crimps and cold welds the end of the tube at the same time, it’s only made in England. I work a lot with vacuum tubes, rather than having to solder caps on every time I cut a tube if I had one of these it would make my life a lot easier”.

So that was the deal, a super expensive hi-tech image store in exchange for a plumbers tool.

We loaded the equipment into the car and set off on a tour of the western part of the divided city. He showed me the Berlin Wall, the Brandenburg Gate and the famous Checkpoint Charlie crossing point between East and West Berlin. Dr Warrikhoff then said he would like to buy me lunch at a very traditional Hungarian restaurant. I felt morally obliged to order a Hungarian goulash, we waited in pleasant conversation over a beer and Pálinka fruit brandy. So amiable was our discussion that the restaurant seemed reluctant to interrupt us by bringing the meal. By the time the goulash arrived, I was famished, having not eaten since early morning. I had just taken the first mouthful when Dr Warrikhoff, now Harald, grabbed my arm.

“Look at the time,” he said “You’ll miss your plane.

With a full plate of goulash on the table, we rushed out of the restaurant and sped off to Tempelhof.

I said goodbye to Harald and hurried into the airport with a small case in one hand and the Huges’ store under my other arm. With scant time to catch my flight, I was allowed onto the plane with little explanation for my hi-tech contraband and without being intercepted by the CIA or worse the KGB. Back in the UK the following day, I thumbed through the Key Industrial Supply magazine and found the tool Harald had described, I ordered one for direct delivery to Lise Meitner Strasse. I never met Harald again, but little did I know that forty years later, back in Berlin, that exact tool would smooth over a particularly tricky political problem I was having with a European Union tech project.

Epilogue:

The film safe baggage inspection development was completed successfully. The first pre-deployment unit was installed at Stanstead as it was the least busy London airport. One day I went to Stanstead because of an equipment problem which only took a few minutes to resolve. As it was quiet, myself and a man from Analytical Instruments asked the security man on the X-Ray machine what he thought of the equipment.

“It’s rubbish,” he said.

“Why?”.

“Because I’ve never found anything.”

“Well, have you had any terrorists through?” we inquired. He just shrugged.

A bus full of tourists turned up for a flight to Uganda and started putting their hand luggage through the machine. The security man scanned the screen complacently. The Analytical Instruments man had an attache-case with a replica 9mm automatic pistol in it, he slipped it onto the conveyor belt. A few moments later, the security man suddenly jumped out of his seat, pointed at the screen and shouted: “There’s a fucking gun in that case”.