Borrowing the Short Magazine Lee Enfield Rifle.

Borrowing the Short Magazine Lee Enfield Rifle.

One summers morning in 1961, I was walking down Highfield Crescent in Brogborough, when coming the other way were Colonel Beasley, his cousin Ray and Frank. The three of them were about fourteen or fifteen, a lot older than me. Two years doesn’t seem much older, but when you’re twelve, it is. I was astonished when they said they were undertaking a clandestine operation and would I like to come along.

Wow! Being asked by the big boys to go on a special mission.

Without a thought, I said, “Yes, where are we going?”. Colonel Beasley put his finger to his lips.

We met on our bikes on the B557 main road and headed off in the direction of Bletchley across the newly opened M1 Motorway. My bike was a lot smaller than theirs, and they kept having to stop and wait for me. About thirty minutes later we got to the Bell pub in Aspley Guise where we peeled off into Woburn Lane. I can’t remember exactly where, but ahead of me they suddenly dropped their bikes on the verge and disappeared. When I got to the spot, a finger beckoned from the bushes for me to follow. We lay concealed side by side peering through a hedge across a field towards an Army Cadet hut. Colonel Beasley started issuing instructions.

“You see that small window?” silence “Are you listening to me, Private Butler?”.

I didn’t realise he was talking to me. “Yes Sir”.

He gave me detailed instructions for what I had to do, finishing with:

“Frank’s the tallest, he’ll go with you to help you get through the window”.

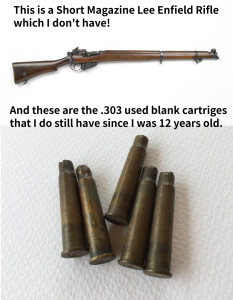

Frank and I ran in a crouch across the open field and dived into the bushes by the hut. The window was in two parts, a fixed pane at the bottom with a fifteen by fifteen-inch window above, hinged along its top edge so it could be propped open by an articulated handle with holes for a fixing stud. Usually, the window would have been secured, but my compatriots had left the handle free, as part of a detailed plan after their Cadet training the previous night. Frank lifted me on his shoulders, and I pushed the window up. While wriggling through the restriction, stretching down my hands to support myself on the sill, and bringing in my legs, it occurred to me that the morning’s meeting was not accidental. I fell to the floor, and the thought passed. I was now focused on completing my mission. I found the door on the right, in the room was a massive steel gun safe. With an effort, I pulled on the brass handle and opened the door. A thin brass shim that was stopping the locking bolts from dropping into place fell to the floor. Propped up inside the safe was a Short Magazine Lee Enfield rifle, on the floor were several five round clips of .303 blank ammunition. I took the contraband, and as I had been instructed replaced the shim carefully when I shut the door. Back on the window sill, I passed the ammunition and heavy rifle down to Frank. Then, like an arched caterpillar, with the help of Frank, I made the difficult head first exit through the window. We ran back with the prize and dived into the tree line. After a quick inspection of the goods, Colonel Beasley slung the rifle on his shoulder, and we made a tactical withdrawal on our bikes along Woburn Lane in the direction of Aspley Wood.

Once in the wood, we concealed our bikes in the bracken, made our way along the main track heading towards the Woburn Sands to Woburn road and then cut off onto a lesser used trail. Once we were deeper into the wood and a good distance from any houses, Colonel Beasley loaded a five round clip into the rifle’s magazine. Within a few minutes my three seniors had emptied the magazine, the place was filled with the sound of flapping wings and other unseen creatures scurrying for safety in the undergrowth. I did as I was told and dutifully collected up the spent cartridges. In the confines of the trees, the air was heavy with the smell of burnt cordite. Shoot and scoot tactics were employed, and the three of them trotted away and turned onto another track. I scampered after them, my pockets jingling with empty brass cylinders. The last thing I wanted was to be lost and alone in this forest. To my relief, once they were a safe distance from the last shooting position they stopped. While Colonel Beasley was fumbling in his pocket for a new clip to reload the rifle, a man stepped out from the trees some way ahead.

“Oh shit!” someone said.

The gamekeeper, with a broken shotgun under his arm, approached us.

(The following conversation sounds absurd now, but it was another era; the 1937 UK Firearms Act raised the age of buying a firearm from 14 to 17, and was in force until the new Firearms Act of 1968).

“Someone is shooting around here, do you know anything about it?”.

With quizzical looks and waggling heads, someone said.

“No! But we did hear some shooting from over there”.

“What’s that then,” said the gamekeeper pointing at the rifle.

“Oh, this. This is a Lea Enfield, but look here” said Colonel Beasley, holding it in the present arms position and pointing to a part of the rifle.

“D P O” the gamekeeper read the letters stamped into the metal.

“Yes, that means it’s for Drill Purpose Only. This gun’s been disabled, it’s only good for arms drill and marching practice.

“Oh, I see. Well, I’d better get off and find out who’s doing all this shooting” and off he went to where they had indicated the shots had come from.

The fact is, DPO did stand for Drill Purpose Only, but what it actually meant was the army’s armourer wouldn’t issue it to a soldier and expect him to hit a target using it, that’s why it was passed down to the Cadets.

Once the gamekeeper was out of sight, we set off at a pace in the opposite direction.

Eventually, after more volleys, we got to where the Woburn Road separates Aspley Wood from Aspley Heath. By this time I was moaning because I hadn’t had a shot with the rifle.

“Look, these blanks can do serious damage or even kill. This is a real rifle, it’s not for kids to play with”, said, Colonel Beasley.

I whined, “It’s not fair, after all, it was me who got it from the Cadet hut”.

“Alright, I’ll show you just how dangerous these blanks are” he retorted.

He looked around, there was a large cardboard box that must have blown off the back of a lorry in the undergrowth. He tore the side out of it and handed me a piece roughly two and a half feet square.

“Now stand over there. Hold it top and bottom and away from you as far as you can”.

He picked up the rifle, pulled back the bolt, pushed it forward and loaded a new cartridge. Standing six feet from me, he raised the rifle and aimed at the card between my hands.

“Don’t look at me, turn your head away”. As I did there was an almighty BANG, my ears rang, my hands stung from the blast, and I dropped the cardboard.

He came over, picked it up and showed it to me. In the centre, there was a ragged hole that looked like a golf ball had gone through it.

“See how bloody dangerous these things are. Let that be a lesson to you, never mess around with blanks”.

After more whining they finally let me take a shot, but someone had to support the barrel because the gun was too heavy for me to hold level. It didn’t kick much, but it was certainly a thrill to shoot it.

By late afternoon we were back at the Cadet hut. I had to do the reverse of the mornings exercise to return the now cleaned rifle. This time I removed the shim to allow the safe door bolts to drop into place leaving the scene seemingly undisturbed. We didn’t really do anything wrong, we only borrowed the rifle and returned it in good order. I suppose technically, you could say, we stole the blanks, but then in our eyes, we were preparing for covert operations to save England in the event of a Russian invasion.

I often wonder what would have happened if I had been caught alone in that hut, and how it would have turned out when the police arrived at my house to question my dad, an Irishman, on why his twelve-year-old son was caught in possession of a rifle in a government establishment.