Lodgers.

Lodgers.

It must have been quite a shock for my mum when she left Rosslare Harbour, Ireland, in 1946 to join my dad in the brickfields of Bedfordshire, England.

Rosslare, with the highest average sunshine in Ireland, is atop of a high grassy cliff overlooking the St George’s Channel in the Irish Sea (Muir Bhreatan in Irish). Its harbour was constructed for the ferries coming from Fishguard, Pembrokeshire, Wales.

My mum’s grandfather, John Boyce, arrived from Scotland around the turn of the 20th century when the harbour was built, he was the block-foreman for the construction of the harbour’s pier. The pier’s storm wall was known as Boyce’s wall when I was a child. John Boyce never went home when the work was completed.

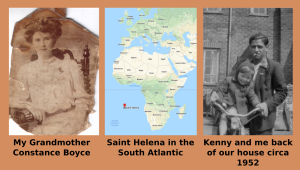

Rosslare was a small village in those days, it had no church, but it did have the Railway Social Club for the other spiritual things in life. From the clifftop by the Harbour View hotel, where the 99 steps come up from the port road, it was a four-minute walk to 1170 Colville Street, the house of my grandfather Ben (Bernard) Boyce. My mum’s cousins Tom and Paddy Boyce lived in Jameson Street behind Granddad’s house. Across the street at 1177 lived my aunty Emma and uncle Richi from my grandmother’s side of the family whos maiden name was Constance Siggins. Constance was born in Bombay India, her father was a soldier in the India Army of the British Raj. Auntie Emma kept a framed photograph on her dresser of him in uniform wearing a pillbox hat. The aroma of curry was not unusual in Colville Street. An elegant looking lady, I never met my grandmother Constance as she died before I was born. Colville Street marked the end of the village then. It backed onto a plantation of trees full of nests and noisy jackdaws that led onto the old Kilrane road.

In those days Rosslare was a small place, that’s not to say my mum came to a metropolis when she moved to England. With just three streets and little over one hundred houses, Brogborough was smaller than Rosslare. The difference was Rosslare was a homogeneous community, my mum knew everyone, and everyone knew her. They weren’t just Irish, they were all Rosslare; well, all except for my lovely auntie Betty who was Welsh.

In contrast, Brogborough was a diverse mix of humanity from across the globe, unrelated strangers looking for work and a new life after the disruption of World War II. However, by the time I was five, Brogborough was a close-knit community, everyone knew each other, and consequently everybody else’s business. Like any community there were enmities, but if you had troubles, there was always a neighbour to turn to.

Apart from a village full of strangers, probably the biggest shock for my mum would have been the air. The sulphurous atmosphere from the brickwork’s chimneys was a far cry from the ozone rich sea air of Rosslare. As a child, I occasionally found my mother softly crying by herself. Over the years, as I came to love Rosslare, her family and friends, I understood the wrench it must have been for her to leave and come to England. However, soon mum’s sister auntie Mary, her husband uncle Steven Susikow and my cousin Bernadette, came first to an old house two miles away on the Marston road, then to 12 Ridgeway Road, Brogborough. I’m not sure where uncle Steven came from, possibly the Baltic States. He didn’t talk about the war other than he’d lost contact with his family. Like many other displaced persons Poles, Yugoslavs, Czechs and Slovaks, he never went home because their countries had become part of the Soviet Union.

With this post-war diaspora throughout Britain, a condition for my parents getting a house was they would have to take in lodgers, not forever but for a few years until housing availability improved.

And so, my mum settled into a new life and waited for her lodgers. Now she had her own home, but soon she would be sharing it with strangers. It would have surprised her to know that her new boarders would soon be setting out from a very different island on their long journey to Brogborough.

1,950 km west of southwestern Africa and 4,000 km east of South American, at coordinates 15° 56 S, 5° 42 W, a tiny speck of an extinct volcano rises 818 metres out of the vast South Atlantic Ocean. You may be forgiven for not knowing this place, especially if history and geography were not your best school subjects. Only 16 by 8 km in size, with a mild tropical marine climate, it is where Napoleon was exiled after his escape from Elba and the resulting Battle of Waterloo. This, the island of Saint Helena is one of the remotest places on Earth.

Sometime in the late 1940s early 50s, two young men from that distant place boarded a ship on its way from Cape Town, South Africa to England. Union-Castle mail ships occasionally stopped at Saint Helena on a two-hour turnaround before sailing on to Ascension Island. Their journey would take two weeks as the ship ploughed its way north around the west coast of Africa and across the Bay of Biscay to Southampton. Like any young men, they would have been both apprehensive and jubilant about this new adventure.

I can imagine their dismay if it was winter when Kenny and Charlie Wade arrived with their cases at 32 Highfield Crescent. With a cloudy sky and damp air holding the acrid smoke from the brick factory chimneys down on the street, Brogborough could be a bleak place in the winter. The houses were cold, in the mornings you had to breathe on the frosted windows to clear them to see out.

Coming from a small coastal community and struggling to adjust herself, my mum understood their feelings. Regardless of the season, they received a warm welcome. I was very young when Kenny and Charlie came to stay, it is now a distant memory. However, I grew to know them well, Charlie moved on to live in Leighton Buzzard, but regularly came to visit. Kenny married Betty Ring, an Irish girl from Brogborough and moved to the next street. Kenny and Betty often came to see us, especially when my dad rented a television, one of the first in the street, for two shillings a week from Simmons Ltd of Bedford. On nights of a big football match, it was standing room only in our house. We lost touch with Charlie, but I have known Kenny all my life. After I married Sandy and moved, and even when we left for Mallorca, I often met Kenny in Brogborough CIU Club on our trips home.

But that was not the end of our relationship with Saint Helena. Around 1960 another two young men with suitcases arrived at our door with a letter for Mrs Butler. Mrs Wade wrote that Kenny and Charlie had spoken very highly of my mother and asked if she could watch over her younger sons who had followed the path of their brothers to England. Bedrooms were rearranged. My sister Ellen got the small front bedroom. Mum and dad moved into the back bedroom, and I ended up sharing the biggest bedroom in the house with my newly acquired older brothers, Georgie and Herbie.

I have fond memories from that time, not least the extra pocket money and Christmas presents from the brothers. One thing I found amusing was the two of them always slept with the sheet pulled right over their heads. With the sheet blowing up and down, it was like having two breathing corpses in the room. It made me think there must have been a lot of nasty insects in Saint Helena.

One time Herbie took an extended leave from his job and took the Union-Castle ship back to Saint Helena to see his family, he was gone about two months. When he returned home, the top of his suitcase was filled with mangos that had ripened on the journey back. That was the first time I had ever seen or eaten that exotic fruit which is so common in supermarkets today. And that’s how it was for the next four or five years until Georgy and Herbie found their own way in the world.

It was an eclectic, cosmopolitan community I was brought up in.

An old African proverb says ‘It takes a village to raise a child’. I had the good fortune to be raised in Brogborough.